Hers was probably the fiftieth or sixtieth door I knocked on that afternoon. The sun had set enough that the white doors on the east side of the street were no longer too bright to look at. A dog barked inside her house, so I knew at least someone heard my knock. It’s always a guessing game: how long to wait before I accept that no one is coming. Thankfully, she answered quickly. She had a go-away face, though, her eyes hard and a tension around her mouth as if she were trying to spit me out.

I introduced myself and my organization and moved into the opening of my pitch before she could cut me off. “We’re a local non-profit that does a lot of environmental advocacy at city council and we’re in your neighbourhood doing some outreach this afternoon. I was wondering if you’re concerned about environmental issues?”

Her eyes hardened even further as I spoke, but her mouth relaxed to form the words with which she planned to send me away. “Well of course I am. Everyone is. But I don’t have time right now, so goodbye.” She shut the door before I could say anything more.

Hardly anyone has time to talk, so I was accustomed to this sort of rejection, especially at “cold doors” where the residents were not already on our member list. The closed door did not bother me, but as I moved on to the next house I pondered this woman’s assumption that of course she’s concerned, everyone is. Because everyone isn’t. That is one thing you learn when you try to talk to all the people on one street.

There were some houses I canvassed where the resident (often an older man) told me that he thinks we need more pipelines or, in one case, that he supports Donald Trump. These are the houses where we are trained to say, “Okay, have a nice day,” and move on, because the chances of recruiting them as supporters are slim. I wonder how the woman at the door that morning would have reacted if she encountered this kind of opposition from her neighbours. Would she have left her door open longer to prove that she’s on my side? Or kept it closed, satisfied that at least she cares, and that ought to be enough?

The vast majority of people seem to stop at caring, alleging sympathy, while still ushering me away claiming that this isn’t a good time. These are people with dinner on the stove or on the table, who are trying to bathe their kids, who just got home from a long day at work, who are trying to watch the game on TV. People who have someone on the phone, who are doing housework, who are just heading out, who aren’t feeling well today, and who don’t feel obligated to make excuses to a stranger. These people are me sometimes too, as I rush past a blue-vested street canvasser with my headphones in, pretending that I’m late to class.

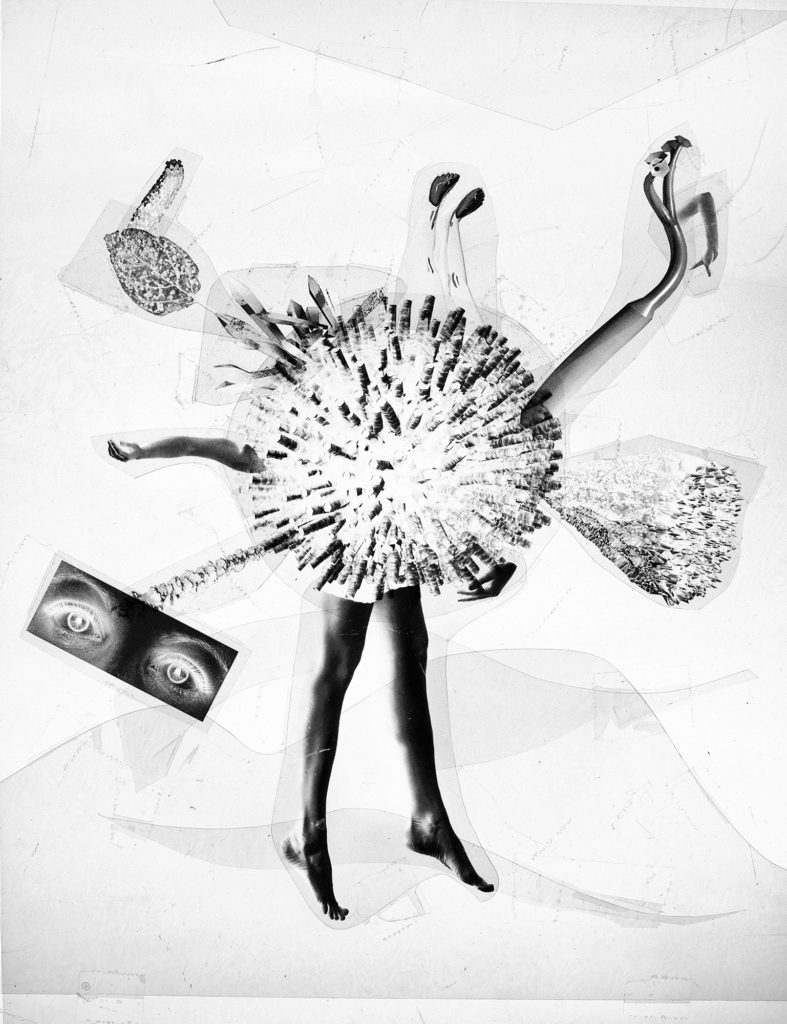

Composite Hybrid by Katarina Marinic

The present is sabotaging the future, and it terrifies me. Yes, the system is rigged by fossil fuel companies and powerful climate-science deniers, but on the local scale, “I don’t have time right now so goodbye” is also a substantial threat to environmental progress. People are so caught up in the quotidian details of getting by that they have no time left to step back and think about solutions to problems that will make it harder to put food on the table and be secure in their home and maintain their health in the not-so-distant future. It’s easier to just avoid the rabbit hole of anxiety. This is both a major obstacle and a call to action for activists.

As another dozen doors shut in my face, or as I burrow deeper into my hood to avoid being stopped for a sidewalk survey, I can’t help but wonder if capitalism did this on purpose. I really do have to get to class on time, just as my canvassees really do have to get their kids to soccer practice. Society pushes us towards fulfilling our individual responsibilities in a way that makes coming together for systemic change highly inconvenient. We are barraged with alarm bells through every form of media, on the streets and in our houses. To breathe, we shut them out.

When I began to get involved in environmental activism in my first year of university, I thought it was about yelling. Get out in the streets with as many people as you can muster! Sneak banners into strategic locations and be disruptive! That way, everyone would have to remember how dire the situation is. It baffled me how people could just go about their lives and not be (outwardly) concerned about climate change. Don’t they know, I thought, that if we don’t do something right now we’re quite possibly going to destroy the planet forever?! The more I talked to people both in my daily life and while canvassing at their doors, I realized that most people do know, yet they oscillate between denial and feeling overwhelmed. Instead of feeling the urgency of action, they just want the chatter to stop.

Imagine silence. No one pressing for solutions, as climate change lurks in the shadows. It would feel unbalanced, a chasm of potential waiting to be filled with the floodwater on its way to our doors. As activists, we are compelled to lead the charge, banners flapping behind us as we rush to stem the tide, echoes of our rallying cry emphasizing the emptiness behind us and in the pits of our stomachs.

No one will follow us if they only hear our alarm but don’t feel heard themselves.

To grow our movement, we can’t rely on simply convincing people, adding more anxiety into their already-busy lives. Yelling louder won’t cut through the noise. I used to go into conversations with potential supporters as if they were stubborn legislators: a verbal bulldozer, determined to stick to my position and not back down. But effective activism is really about listening. When I listen to people’s concerns, I find that most people already have the motivation to do something.

At the door, it was my job to show people how giving to my organization was one way to make a small contribution to environmental work, and that’s not untrue: for those with more money than time, donations to community organizations are vital to move the cause forward. But off the clock, there are so many other things that people can do. They can vote. They can vote with their money. They can get out and protest. They can go to a beach cleanup. They can have a car-free day or a meatless Monday or bring a reusable mug and cutlery in their bag. Deep into a conversation with one young mom about her efforts to avoid disposable diapers, I fumbled for any information that she didn’t already know, afraid of losing her interest. But in the end, she donated not because I led her to care, but because I stood with her in her struggle to work out her path, accidentally managing to assure her that we are in this fight together.

Yelling about how everyone needs to be actively involved in the solution often rips the environmental movement apart. We are caught in the paradox between being palatable to centrists and acting fast enough to protect marginalized communities. Ironically, these arguments can keep us from both immediate action and slowing down to listen to our neighbours.

As activists, we can’t get so caught up in our own concerns that, just like the woman I met at the door, we don’t have time when people want to talk. As a movement, we can’t let the climate crisis become our everything, causing us to shut out the other parts of life that threaten to overwhelm us. We can’t assume that we have the support of the entire left without doing anything to include them. Closing the door keeps us from building support and making progress. Instead, let’s take a breath. Lock eyes. And listen to how we can move forward together.