It took me four days to read Soraya Peerbaye’s Tell: Poems for a Girlhood (Pedlar Press, 2015). By day three, I wasn’t sure I could follow through, so acute was my fear and respect for the tide of pain and loss on nearly every page.

It took me four days to read Soraya Peerbaye’s Tell: Poems for a Girlhood (Pedlar Press, 2015). By day three, I wasn’t sure I could follow through, so acute was my fear and respect for the tide of pain and loss on nearly every page.

Tell honours Reena Virk, assaulted and murdered by her peers in 1997; she was 14 years old. I was 14 in 1997, as well; our birthdays are only weeks apart. Perhaps “I’d have been her friend” (“Trials,” 10). In Grade Nine, I didn’t know any girls from South Asian families, but I had girlfriends who loved clog boots, who wore pleather jackets; girls who shouldered rumours, reputations, and threats too heavy for their age, their hearts and bodies—girls, in many ways, like Reena.

Peerbaye’s brilliance—and yes, this poetry is transcendentally brilliant—is her commitment to image as memory, and memory as empathy. Each poem quietly prepares you for the next with its own “silt, shells, bottles, trash, eelgrass” (“Silt,” 9)—its own traces of oncoming violence. This evidence hides away in your shoes, sticks to your skin, does its work of cutting and chafing as Peerbaye goes on to ask you, gently but insistently, to consider the specifics of Reena’s pain and death: how it is that her clothes became “saturated… soiled” (“Current,” 4), her skin “slackened, sloughed” (“Washerwoman,” 11), and what it means when pathologists find stones in the mouths of young women drowned.

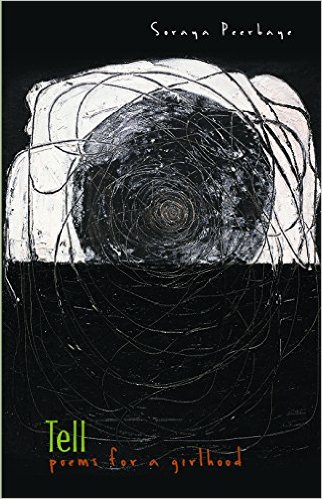

Perhaps Karine Guyon’s beautiful cover art is a warning: its splintered, tangled, spiralling web of shadow, descent, moonset. But like the whorl of white paint across the top half of Guyon’s There is Light, Tell’s hopeful and forward-looking core shines through for the reader who perseveres. In the section “Who You Were,” Peerbaye’s poetic speaker gives us another facet of Reena by reflecting on her own girlhood—her own experiences as a South Asian teen growing up in Canada. There is “pain, depression, sleep” (“Safety,” 6), and the “verdant grief of girls” (“Tremor and Flare,” 13), but also “sweet water, sweet stones” (“Lagoons and lakes,” 10)—the redemption of debris.

And in the book’s final poems, we find resplendent parting gifts: the Lekwungen story of Camosun; the persistent “life in these waters” (94); bones, tools and fragments “four thousand years old” (“Tillicum Bridge,” 11). These are traces of history and healing, and Reena’s call to rest in the land.

Tell won the 2016 Trillium Book Award for Poetry and was a finalist for the 2016 Griffin Poetry Prize.

See also “Reena” by Carole Glasser Langille.