Blood is a deeply weird word. Its strange proto-Germanic double-O ends in a palpitation—a thud—a footfall on dark earth, while its spectral onomatopoeia hums of haemorrhage, not haemostasis.

Blood is a deeply weird word. Its strange proto-Germanic double-O ends in a palpitation—a thud—a footfall on dark earth, while its spectral onomatopoeia hums of haemorrhage, not haemostasis.

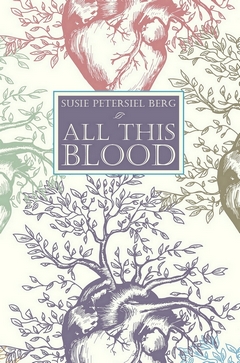

In her new poetry collection All This Blood (Piquant Press, 2017), Susie Petersiel Berg uses the process of haemostasis—how the body stops bleeding—to conjure wounds that have closed over but still sting in the shower, against the sheets or out in the cold. Berg’s poems are reminders that blood is always with us, even when we don’t taste its iron or call it by its deeply weird name.

All This Blood is organized according to the three phases of haemostasis: vascular, platelet and coagulation. Her title and guiding metaphors signal, in tandem, the potential for blood in every poem; as the “process” unfolds, this language becomes a kind of forensic, empathic dare to the reader.

The vascular phase begins as soon as a blood vessel is cut. The tiny muscle fibres in the wall of a damaged vein or artery, stimulated by sympathetic pain receptors, contract in order to limit blood loss.

Each poem in “The Vascular Phase” is fragile, precariously balanced, threatening laceration. Or, in the case of “Falling,” injuring its subjects multiple times, their body parts—“lungs,” “flesh,” “bone,” “snakeskin,” “arms,” “breasts,” “head,” “teeth”—exposed and glaring in lean stanzas.

Potential weapons and sources of injury appear throughout “The Vascular Phase”: rock faces, stones, stairs—even bullies. My favourite piece in this section, “All This Blood,” fulfills its (and the book’s) threat of excess with a gruesome injury beautifully rendered: “His forehead spills like a cup”—the bloody consequence of a deftly thrown rock.

During the platelet phase, specialized fragments of cytoplasm begin sticking to blood vessel walls, collagen fibres, and each other, forming a temporary blockage. Ideally, this slows bleeding further and allows healing to begin in earnest.

Initially, I was surprised and a bit puzzled by the number of dating and relationship poems in “The Platelet Phase.” But then again, of course: dating is a cycle of attempts at bonding; damage and healing; and the risk of being sticky or getting stuck.

This middle section includes “The Art of Porn,” which I initially found exasperating in its polished simplicity and directness—Where’s all the mess and blood?—but ultimately rewarding. Its flushed nipples, lips and erections up the ante on All This Blood’s sanguineous dare. Get out the luminol and the blacklight; turn down the sheets; press the pause button; lean closer.

And then there’s the florid mess that high-production-value mainstream porn omits and implies: the real blood brought to the surface in all kinds of real sex. Traces of menstrual fluid; torn skin; ruptured capillaries; bruises intentional and otherwise.

The coagulation phase sees the platelet plug reinforced with fibrin. Clotting factors in the blood become active. Bleeding stops; the work of repairing skin and tissues is underway. Yet “The Coagulation Phase” includes Berg’s rawest, most wounded poems. Death, hospitalization, family tragedy: the kind of healing that takes years.

“The Existential Debate,” “In the Museum of Your Last Day” (first published in Understorey Magazine in 2015) and “This Is My Note” work on me—are still working on me—like the cells, factors and feedback loops that combine to arrest haemorrhage. They knit into a portrait that I recognize: young men in my life who’ve struggled against the limits of pain, loss and meaning.

All This Blood, in both sound and deed, invokes another double-edged old word with similar ancestry: flood. Berg’s poems track wounds and healing as if they are the edges of floodwater. She approaches the crest to collect blood’s revelations, necessity and threats so that we might encounter blood’s power and universality at a safer—though never quite safe–—distance.