Dear City Friend,

It’s 6:45 on June 20th, and while the temperature is dropping, there are still hours of daylight left. I felt moved to write you a letter and tell you about the snowball bush in full bloom right now and the little worms we found on a curled leaf, presaging the annual devastation that blights this intrepid feature of our yard.

I want to tell you about the lilacs, French and Korean, that are sending out their unmistakable perfume into the evening air, and the huge yellow iris that burst forth this week, and the much smaller wild blue irises that we rediscovered today blooming on the rocks just a few feet from the Bay of Fundy.

I know that you would love the foamy white bridal wreath spirea (an anniversary gift to us the year they legalized gay marriage, remember?) and the dozens of upright pink and purple lupines, signature flower of Nova Scotia, in full and glorious bloom right now. And so much more. Like the little raccoon who has started raiding our hanging bird feeder, all on his own, two months after we chased him and his mother and siblings away.

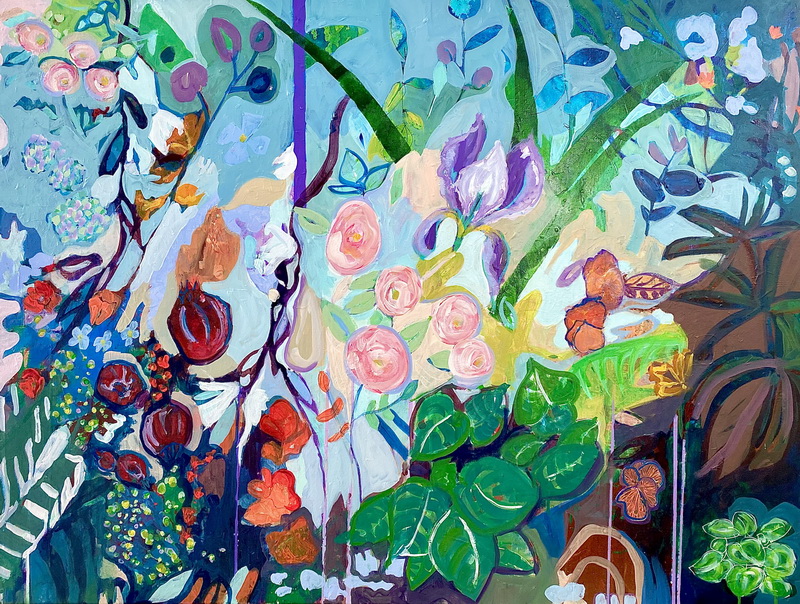

Fantasy Garden by Jessica Ruth Freedman

All of this feels like news to me, although probably not to you. I remember living in the city, being engaged with social life and constant action, working on important issues, attending theatre and dance productions, films and events. Going out, keeping up, meeting up, on the go, living the life, living the news. That has continued to be your reality, at least up until this pandemic stalled city life in a way that suddenly brought your pace much closer to ours—although without our natural benefits.

Decades ago, when I lived in the city, I met a woman who did not. Her letters schooled me in a more rural kind of news. For her, news was when the chickadees that she’d been watching for a month stood aside and let their fledglings fly free from the nest. News was when the onions she’d planted were ready to pick. News was fresh snow in the nearby woods and seeing an animal, mink or marten, just living its life out there.

And now I live out here too, in rural retirement. At first, back in the eighties, we didn’t even have a phone and my partner, the owner of this tilted plot of land on the shore, was content to occupy a mere ten percent of it. Her wheelchair was totally incapable of navigating the rest, despite keeping everything mowed in a grand illusion of flatness. It’s all grown up with trees and gardens now, and retrofitted with accessible pathways, landings and decks, so she really can get just about everywhere she wants to go.

Change started with basic telephone, soon followed by internet, cellphone service, and then Netflix. Suddenly, it seems, we are no longer remote. Rural, yes, but not remote. This pandemic year, we “attended” the Toronto International Film Festival virtually. My inbox is full of alarming news of fires, floods, drought, and the oppressive conditions in which people live around the globe. Not to mention the plight of animals, large and small. Rural news and urban news are no longer so far apart.

Sometimes out here in our lush surroundings, we struggle to stay connected to the wider crises but we do notice things. Fewer birds this year, yes. And although we know that insect populations are declining, we still get bugged. Ticks are plentiful. We do miss our bats, all of whom succumbed to white-nose disease a few years ago. We notice far fewer fishing boats in the water. No whales. No gypsum boats. Still no tidal power. A major wind power project defeated by timid souls worried—justifiably?—about bird strikes and brain effects. Still talk of big fossil fuel projects as the solution to economic depression. Still outright war at times between settlers and Indigenous fishers. But still no noticeable change in tide levels on our doorstep, or the basic facts of what happens when seeds go in the ground.

It’s later in the evening now, on this longest day of the year, also our thirty-first anniversary. We had a delicious seafood dinner, watched a whole movie, then marvelled at the fact that it was still not fully dark at 10:30. A waxing gibbous moon contributed its reflected beams, lengthening the day even further. So enough for now, dear friend. I do hope you’ve stayed well. I hope the pandemic has spared you and your loved ones, and if not, I’m so sorry. We are easing back into social interaction and, as we do, we hope that maybe we’ll have occasion to welcome you for a visit out here once again.

In love and solidarity,

Your Rural Friend