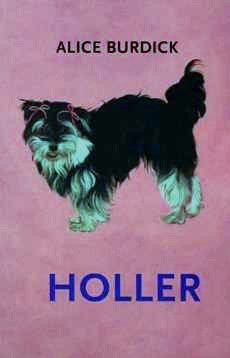

I met poet Alice Burdick on a snowy morning at the Biscuit Eater Café in Mahone Bay. We sat in winter sun made cozy by the scent of baking, Latin tunes on the CD player, and shelves stacked high with books, including Alice’s latest collection, Holler.

I met poet Alice Burdick on a snowy morning at the Biscuit Eater Café in Mahone Bay. We sat in winter sun made cozy by the scent of baking, Latin tunes on the CD player, and shelves stacked high with books, including Alice’s latest collection, Holler.

We planned to talk poetry and motherhood but first took a few minutes to enjoy lattes, muffins, and marvel of leaving the house. It has been a cold winter in Nova Scotia with a lot of storms and school closures, times Alice spends at home with her children, Hazel, aged 6, and Arthur, 4.

Alice Burdick: I usually write at home, even when the kids are at school, but I do miss those days of leisurely writing in cafés like this one.

Katherine Barrett: When did you start writing poetry?

Alice: I took an extra-curricular writing course in high school called The Dream Class. It was run the by the Toronto school board, taught by Victor Coleman, and introduced me to the major poets and poetry movements of the twentieth century. I got hooked and later started making my own chapbooks—complete with hand-painted covers and pages—and selling them at book fairs and bookshops.

Katherine: And you’ve published a lot since then.

Alice: Yes, several chapbooks, three full-length poetry collections, and poems in literary magazines across Canada.

Katherine: How has motherhood changed your writing practice?

Alice: Other than spending less time in cafés? I’m much more focused than I was before kids, I just sit down and write. I treat it like a job and that way I’ve kept writing straight through motherhood, even when the kids were babies. I have to write to feel fully human.

Katherine: Your latest collection, Holler, contains many poems about children and mothering.

Alice: More than my previous collections, yes, and readers have said Holler is my most accessible book. I’m not sure how those two points are linked but it likely has to do with the immediacy of motherhood.

Body House

(from Holler)

Hazel stands in front of me

and points to her eyes.

They are windows, her ears,

they are windows, and her mouth,

she says it’s a door.

Her body is a house,

and she’s home

for now.

Katherine: Tell me about “Body House.”

Alice: My daughter, Hazel, was about three when she came to me with these pronouncements about her eyes, ears, and mouth. I saw her trying to situate herself, her body, in the world; trying to process the information that flows in and out. Three is such an innocent age, free of insecurities about bodies but I know that she’ll one day become aware of how others see her. That’s why I added “for now.”

Ghost Feet

(from Holler)

Please make me a book

from salad and tears. I cry at condiments.

My ghost feet light up the sidewalk.

Will you forget a book or a person so easily?

Arthur makes a series of sounds

that will one day be words.

He gets his point across

the floor, straight to the cat’s dish.

Katherine: To me “Ghost Feet” is about that crazy headspace of motherhood. Why am I crying at condiments? No, my kid is crying at condiments. We’re both crying. Never mind because there goes Arthur to the cat dish….

Alice: I’d say a lot of the poems in Holler share that quality: the brain on tangents brought home by the physicality of parenting. But “Ghost Feet” actually started with Michael Jackson. A friend challenged me to write about him; a “literal” video for Billie Jean and the line “my ghost feet light up the sidewalk” stuck in my head. So the poem is a reverie of sorts: the beauty of life; our quick acceptance of its disappearance; and the everyday strangeness of kids and parenting.

Katherine: What are you working on now?

Alice: I have a new poetry manuscript in the works. I’m also trying my hand at collaborative fiction, co-writing with another author. And now that the kids are a little older, I’ve started carrying my notebook around again, taking notes. We’ll see where it all goes.

Another treat! Thank you both.

Pingback: Mother’s Day Reading at Lexicon Books |