Many moons ago, when I first started reading books about feminist theory, I ran across a chapter on menstruation and oppression. Like all young women I knew at the time, I’d hidden pads and tampons to make furtive trips to the washroom. I’d smiled and carried on through period pain. I’d spent far too much of my student budget in the “feminine hygiene” aisle. So the words menstruation and oppression seemed a logical fit. I kept reading.

The chapter suggested ways to free ourselves from the stigma and confines of the period. Quashing stereotypes and jokes about PMS was a good start. Advocating for reasonable prices and tax-exemption on menstrual products—I’d buy that. Giving up wasteful industrial products completely and sewing our own. I wasn’t much of a sewer, but sure.

The arguments made a lot of sense—right up to the final suggestion, a recommendation sufficiently ludicrous and thought-provoking that I’ve remembered it for decades. Forget “managing” your period, the author said. Just bleed freely.

The idea that women should not try to stem blood flow was new to me and I failed to see how it could possibly be liberating. Who would haul all that extra washing to the laundromat? Who would hire a free-bleeding chef or housekeeper or surgeon? Who wouldn’t stare at a free-bleeding shopper in the check-out line?

And yet free-bleeding isn’t new—or old. Or even that ludicrous.

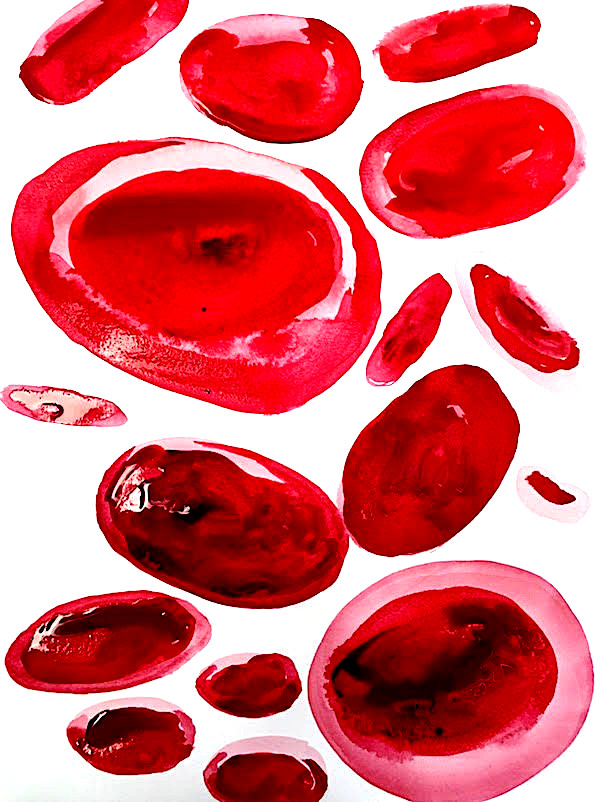

Blood Red by Michelle de Villiers

The historical record on menstruation is, shall we say, spotty (most history is recorded by men), but it’s believed that women have bled into layers of clothing for centuries, simply because they lacked the time, resources or pressure to do anything else. Pads and tampons were developed in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, but a short and more overt free-bleeding movement arose in the 1970s, partly in response to toxic shock syndrome. The more recent revival of free-bleeding is sometimes attributed to an infantile, anti-feminist hoax but is more accurately a serious and conscious decision by some women to compete, practice and create art while bleeding.

So, yes, voluntary free-bleeding was—and is—a thing. These days, it’s not the norm but the women who practice it, whether for personal, environmental or political reasons, have helped to start a discussion, made a point. And for the rest of us, that discussion is the point. I may never be ready for free-bleeding but I’m most certainly ready for free-speaking.

There are over 3.5 billion women in the world and most menstruate throughout their adult lives. That’s a significant part of human history, society and culture currently confined to the bathroom stall. So can we talk about the cashier who is given a four-hour shift without a break? About the student who can’t leave the room during a three-hour exam? Can we talk about how displaced or homeless women can maintain dignity when society pretends periods just don’t happen? Can we recognise conditions such as endometriosis (my spell-checker doesn’t even know this word) as nothing less than a chronic disability? Can we stop disguising pads and tampons like some sort of contraband and aim for open-carry?

This issue of Understorey Magazine is all about blood—free-speaking about its many forms and the many ways it affects women’s lives. Through literary writing and powerful visual art, we share stories about the blood of the uterus and the blood shed, both literally and figuratively, during conception, miscarriage and childbirth. We hear of the blood that flows throughout our bodies and how that flow may be interrupted by something as tiny as a “delinquent” valve or as looming and eternal as illness and death. Several authors write of blood unleashed by intolerance and hatred but also through love and friendship. And we look beyond individual bodies to explore blood shared across generations, how bloodlines carry secrets, and how secrets revealed—secrets spoken—can empower.

Please enjoy, reflect and share.