Q: How many feminists does it take to change a light bulb?

A: That’s not funny.

Which is funny, right? Or not. The relationship between women (and we mean all those who identify as women) and humour—as well as laughter and comedy and even smiling—is complicated. It grows out of life experience and personal taste but is also a product cultural expectations and gender norms.

Humour is highly individual but also deeply influenced by society.

There is, for example, that persistent societal notion that women are simply not as funny as men—hence, the feminist light-bulb joke and many, many variations of the punchline. This notion was recently explored in a (decidedly unfunny) systematic quantitative meta-analysis, with the finding that, indeed, men’s Humour Production Ability is higher than women’s.

Consistent with this stereotype is the caution that women—because they aren’t funny—probably shouldn’t try too hard. It might go very badly. Another recent study suggests that telling jokes in work presentations increases the perceived status of men presenters, but lowers that of women presenters. Why? Because a joke told by a man is interpreted as helping him get the work-related message across; the same joke told by a woman is interpreted as disruptive or as compensating for her poor work skills. Same joke: funny, not funny.

The women-aren’t-funny idea appears to be further supported by the gender gap in stand-up comedy. Men get far more bookings, more stage time, and more pay than women or gender-diverse performers (see #onewomanonthelineup).

But we know it’s not that simple. Of course. Laughter, humour, comedy: not that simple.

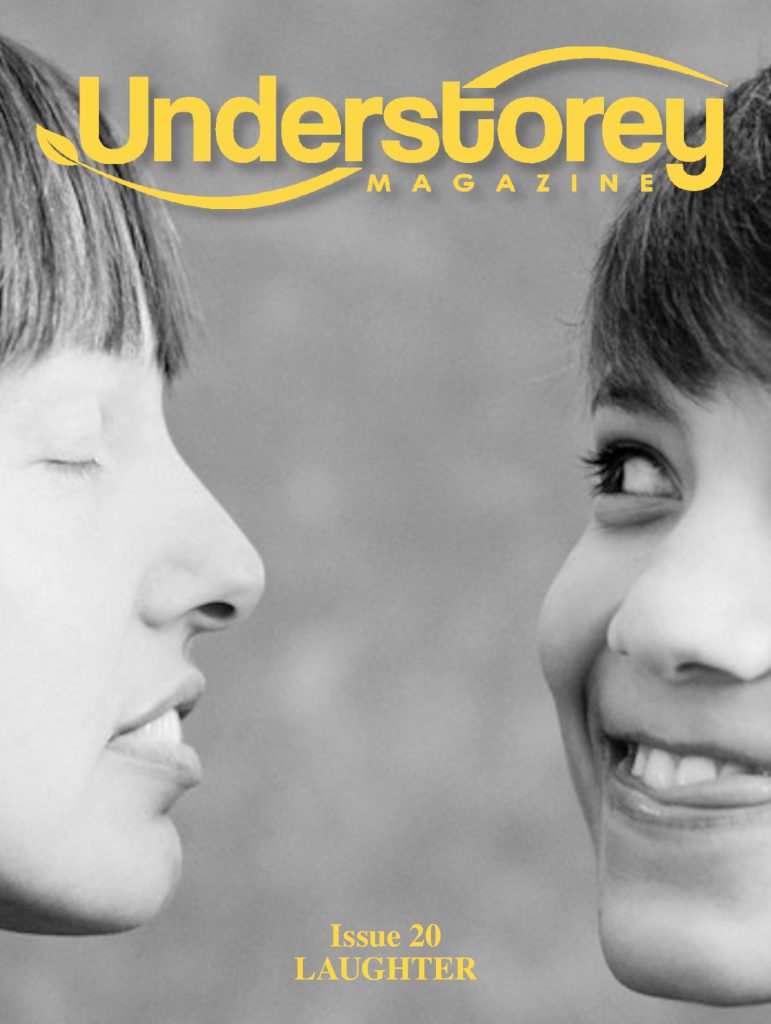

Laughter. Photography by Heidi Jirotka

with assistance from Dante Jirotka.

To start, the comedy gender gap stems in part from the fact that most producers, the people who book the shows, are men. It may also be related to the very interesting finding that while women tend to appreciate funny men, men tend to appreciate women who find men funny. In other words, there’s evidence that women generally appreciate humour production (funny people) whereas men generally appreciate humour reception (people who find them funny). So, yeah, landing a booking in comedy can be tough indeed.

Then there’s being brave enough to tell our own stories in our own way, place, and time. The authors of meta-analysis cited above acknowledge they did not look at cultural differences (how humour is created and received in non-Western cultures) or differences in types of humour (the snappy one-liner versus the longer, more complex story). They also note—and this point is crucial—that women interacting with other women may create a completely different scenario, humour-wise.

Women may find other women funny.

Given that women-identifying folks comprise roughly 50 percent of the population, this statement should be enough to book a woman headliner and fill a venue with laughter. And it’s true, the stories told in that venue may not resonate with all audiences—stories about motherhood, bodies, anger, loss, that ever-present gender gap, feminism, #metoo, and, yes, even menopause. Stories that might be jarring or scary or subversive or sad, as well as very funny.

Because, as this issue of Understorey Magazine shows, laughter can mean many different things. Laughter can derive from the fleeting absurdities in life or from frustration at a system that seems resistant to change. It can grow out of very personal fears or widespread misinformation. Laughter can be a form of resistance or even insurrection. It can offer a new way to see the world or a new way for us to see ourselves.

As Fazila Nurani writes, and as our cover art also suggests, laughter is always shifting to fill many different spaces. Especially in difficult times, like this past year, laughter is therefore powerful and emancipatory. It can bring us together not simply in reaction—the end to a funny joke—but as action. An astonishing twist. A new beginning.

Thank you to all of our contributors for sharing their stories and their visual art. Thanks also Heidi Jirotka and her two children for collaborating on our wonderful cover image.

Enjoy and share!

About Katherine Barrett

About Katherine Barrett

Katherine Barrett is the founder and editor of Understorey Magazine.

About Natalie Meisner

About Natalie Meisner

Natalie Meisner is a writer from Lockeport, Nova Scotia, and an Understorey advisory board member. Natalie’s plays have been produced across the country and have won numerous awards. She is the current poet laureate for Calgary.

About Heidi Jirotka

About Heidi Jirotka

Heidi Jirotka is a natural light photographer with over 25 years experience. Although her initial focus was on newborn and child photography, her portfolio is now diverse. She has worked with Chapman’s Ice Cream since 2012 and is now their official, commercial photographer. Heidi lives in Bridgewater, Nova Scotia, with her husband and their two children. See more of her work on her website, Facebook, and Instagram.