Earlier this year, as Covid-19 spread throughout the world, reports surfaced about the design and fit of personal protective equipment, or PPE. Even the smallest sizes of PPE were too big for many women working on the front lines of the pandemic. The PPE was designed for a generally larger male body. The technology was biased.

Later this year, as Black Lives Matter protests gained strength, many reports emphasized what has been known for years. Police surveillance—which has led to police violence—depends on facial recognition technology. And facial recognition technology misidentifies Black faces more often than white faces, up to ten times more often. The technology is biased.

During these and other world-changing events, people turn to the Internet for vital news and information. But pop-ups, animated GIFs, autoplay, and other website clutter mean people with epilepsy, autism, and other physical, developmental, and cognitive challenges can only read for a short time, or not at all. This technology is also biased.

But can technology be biased? Can chunks of metal, plastic, and silicon be sexist, racist, ableist?

We tend to think of technology as non-human by definition. But technology is, of course, designed, produced, tested, and marketed by humans. And in the tech sector, most humans are men; in North America, at least, they are mostly white men. Available sizes of PPE are based on human assumptions about “typical” healthcare workers. The algorithms that run facial recognition technology are coded by humans with experiences in particular families, workplaces, and communities. The design of websites depends on goals and values, often the uniquely human goal of making money. All of these assumptions, experiences, goals, values—in other words, biases—are built into the technologies we use every day.

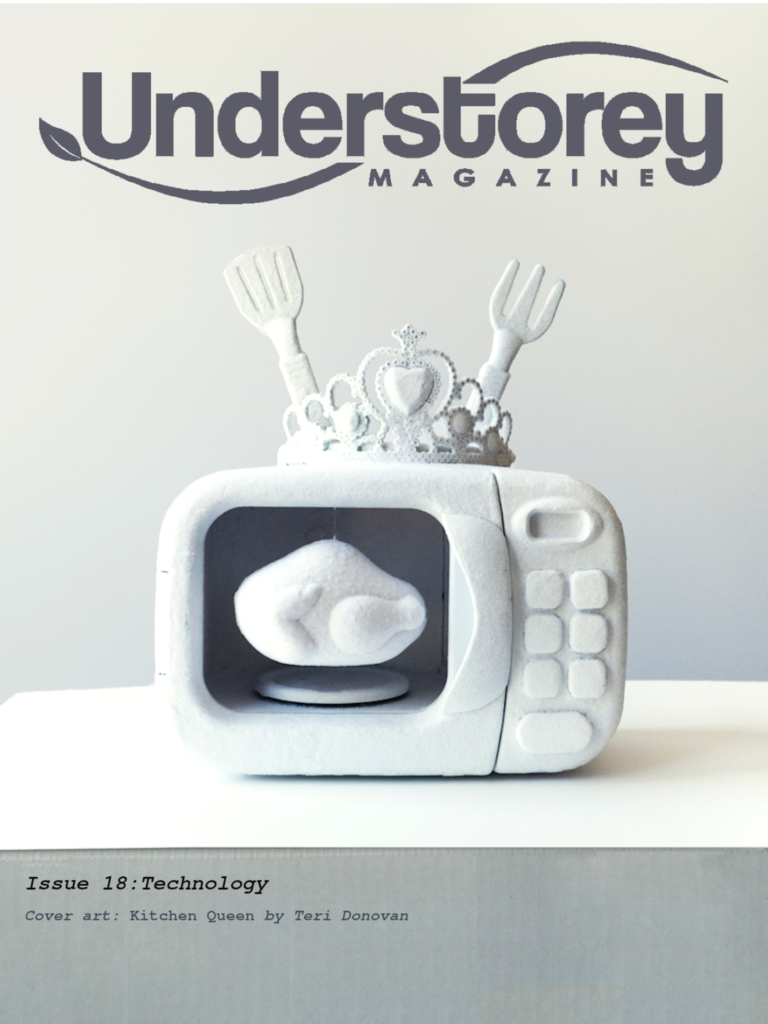

In this issue of Understorey Magazine, we explore at how technology, with all its biases, affects our lives.

How might something as simple as a salad spinner, as familiar as a karaoke machine, or as complex as computer-generated haiku forge conversations across generations and cultures?

How do the features included on a fitness tracker or the tools needed to adjust a wheelchair facilitate or complicate wellbeing?

How might technology connect us directly and intimately to our very identity? Or to our faith?

Answers to these raise questions further questions about who is involved in creating technology and about the barriers—everyday, systemic, colonial—to greater inclusion in science, technology, engineering, and math, or STEM.

Together, the writers and artists in Issue 18 suggest that technology serves us best when the human elements are made visible. When we acknowledge that technology arises not from isolated individuals or autonomous companies but from complex social, cultural, and political systems. When we see that technology does not have a “user” but functions in a network of parents, caregivers, teachers, mentors, Elders, and many others. When we accept that technology is not a thing but a process and work toward technologies that enable without subjugating, that engage our passions but not our compulsions, and that help us understand ourselves by giving voice to many.

Thank you to our cover artist, Teri Donovan. Teri’s Kitchen Queen (plastic toys assemblage, spray paint, fishing line, white flocking) provides the perfect image for the many themes explored in this issue.

A special thanks to the Alexa McDonough Institute for Women, Gender, and Social Justice for their continued support of Understorey Magazine and for providing funds for this issue.