My period arrived when I was fourteen, announcing our future together by settling into my pelvis on a nest of corroding nails. I spent days in bed every month, curled around a heating pad, wondering at the euphemism of “cramps” because what I felt was a deep, greedy, constant pain. Eventually I realized I wouldn’t be able to take time off work every month in the “real world” after high school so I saw a doctor. Loathe to mess with my hormones and go on birth control, with its off-label benefit of easing menstrual symptoms, I accepted prescriptions for anti-inflammatories and painkillers instead. They didn’t work though, and eventually I succumbed to birth control. My auntie laughed at the indiscretion of a home video I’d made, the pills sitting on my bedroom headboard in full view. But I wasn’t using them because I was having sex so it hadn’t occurred to me to be more discreet.

After high school, the pill and the disposable heating pad stuck to my abdomen under my uniform made my monthly pain bearable enough that I could work my serving shifts, in the way that one either slices their tender knees and hands crawling over jagged glass toward bread, or starves. The gynecologist scheduled me for a laparoscopy so she could explore my female interior for fibroids and endometriosis. The good news: she didn’t find anything. The bad news: she didn’t find anything. “Don’t worry,” she said, “most women find their symptoms get much better after they have children.” I clung to that promise for over ten years.

Then, one early morning, bracing my sharply contracting underbelly beside the bed, I told my husband it was time to go. I phoned the rural hospital and a nurse met us at emergency with a wheelchair. “I forgot what this feels like,” I told her, between contractions.

“Oh, I thought this was your first baby,” said the nurse, checking her notes.

“It is,” I told her, “but this is how I feel when I have my period.” I was six centimetres dilated.

*

The gynecologist was wrong about my symptoms improving after childbirth—they got worse. Where I’d always had physical pain before, now I had other symptoms too. I could hardly focus, remember things or process information; writing newspaper articles required immense mental energy and I was still not sure they made sense. My breasts overflowed my bra, beginning to ache a week before my period and pushing pain into me with every movement throughout the day. I developed a chronic sore throat for two weeks each month that coincided with my cycle yet with my esophagus full of camera, the ENT told me it looked fine. I wanted to dig my nails in at the temples of every person I came across and tear the flesh down their face in strips, while simultaneously wanting to weep for all the beauty in the world. I was constantly nauseated during my period. I saw black. I fantasized about laying on the asphalt in front of our house, waiting for a truck to run me over. I breathed through the uterine contractions pushing fallow blood and clotted tissue from my body, just as I’d breathed through labour. I couldn’t stand to be talked to or touched so I perched on the basement couch clutching my hair, knuckles against my scalp, rocking myself; my husband and kids stayed on the upstairs floor, just so we could survive each other.

I wore a patch on my arm to stop my period completely but had breakthrough bleeding all the time. I saw a gynecologist who promised me a solution and learned seven months later he’d closed my file. I met with the best acupuncturist in the city, unable to watch while he tapped needles into my body. I endured visceral manipulation, the practitioner flirting with me while he kneaded my naked abdomen. A pelvic floor physiotherapist probed my vagina with her fingers, to work tight muscles she couldn’t access otherwise. I met with another gynecologist who suggested I get more sleep leading up to my period. A cardiologist confirmed I’d developed a fainting condition; it was my husband who noticed the episodes usually happened during my period, probably from the loss of blood volume. I heard a chronic pain doctor tell me that I might not be able to fix my period problems and that my period was a disability for me.

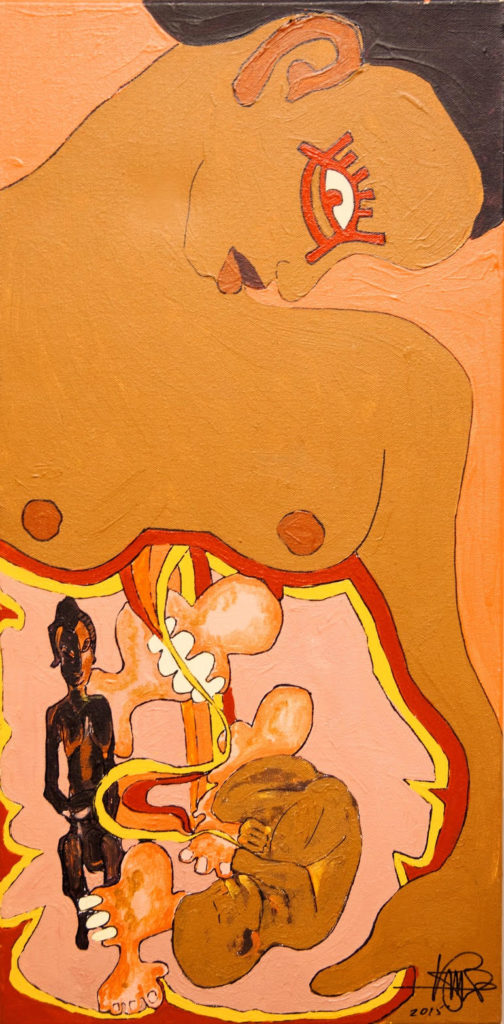

The Fetus, the Fibroid and the Fertility God by Kim Cain

We already planned our social lives around my period; on the advice of the chronic pain doctor, I began to plan other things around it too. I told my editor there was one week a month when he would get less work from me. My husband drove the kids to school and got to work late rather than me pausing every few steps on my way to the van to retch or collapsing onto the floor at the preschool entrance again. But my period didn’t always honour our twenty-eight-day anniversary and sometimes, even though I planned ahead for months, I still had to cancel work commitments or family outings when my monthly flu breezed in three days early or two days late.

More than one doctor recommended a hysterectomy but major surgery comes with its own potential complications that I wasn’t willing to undertake. And a uterus is a place-holder in a woman’s body—I had read about post-hysterectomy women whose other internal organs had squatted into the vacancy left by the former tenant, leading to other issues. Besides, the relationship between my uterus and me was far too complex to sever with a scalpel.

I scheduled an appointment with a new naturopath, made it for when I would have my monthly flu; I would have to claw my way to him with hands and nails of will instead of cells, but I knew he had to see me in that state. I had a suspicion, a theory that was more intuition than science. I had never spoken it aloud before. I was beginning to wonder: Is my uterus contracting so hard because it’s fighting the memory of something?

When my mother was a child,

she was raped in her home,

repeatedly,

over years.

Her mother was raped before her,

in a time past.

Is it possible the pain and trauma of their most intimate, feminine parts being assaulted has been passed down through their genes, so that my own most intimate, feminine parts rage against the unnatural abuse of the pleasure and life-giving purposes for which they were intended? Does my uterus cringe every month as my mother’s must have, as Grandma’s must have? Have their anguish and unheard cries echoed along twisting DNA strands into our futures since?

I gathered the energy to get out of the van and walk into the naturopath’s office, mumbling a sorry for laying my head on the counter as I checked in. Then I sagged on his office chair, depleted, aching. I told him of my symptoms and that if giving birth naturally without drugs as I had was a ten on the pain scale, I run at a seven or eight during my period.

Then, with my eyes on a poster across the room, I revealed the abuse in my women’s history, asked him if it could be related to my menstrual issues. “My God,” he said, shaking his head, “I’m so sorry.” He took off his glasses and wiped tears from his eyes, reaching for a tissue. “Of course it’s related,” he said, “we are souls first and bodies second.”

Sometime after that, in a newsfeed, I first heard of epigenetic inheritance—the genetic imprints of trauma passing from one generation to another via DNA markers—and the scientific research suggesting it exists. What if traumatic experiences can be inherited through generations, as an evolutionary adaptation, like a predisposition to the fear of spiders can be? What if muscle memory can travel the nucleic time machine into the future? My own anecdotal evidence confirms it’s so.

I think of my daughter’s uterus forming inside my uterus—the tiny cells knitting themselves together to become her uterine wall, nutrients and oxygen passing from my bloodstream to hers, directly fueling her development. But is that all that passed along, just some vitamins and good fats? Or did our bodies exchange other information in the rich, red, velvety room of the placenta, whisperings of my mom’s nervous breakdown when I was a teen, triggered by the abuse she’d endured as a child? Or mutterings of Grandma’s own breakdown, when my mother herself was a child?

My daughter is eight now, closer to getting her first period than farther. What will it be like for her? Among two generations of family members, most who know of the abuse don’t acknowledge it; some talk a little; others don’t know at all; and some feel the undercurrent that exists, even if they don’t know why. My grandmother knew of my mom’s abuse, because Mom told her.

Then Grandma ordered her never to mention it again,

spanked her,

sent her to confession

and, inevitably,

back to her abusers.

Denial and secrecy about abused women compounds the trauma. Could it be compounding cyclical pain in their female offspring too? I am not the only woman among two generations of my family who suffers each month—one imagines hanging herself, another lost a friend after too many cancelled plans, others have chronic sore throats, and on it goes. As a teen, my mother herself got very sick every month but was forced to go to school still, creeping off instead to her grandmother’s where she could at least rest.

The muzzling of women about rape suffocates their hearts and minds, distorts their wombs into shadowy caves. And the next generations of hearts, minds and wombs are models of theirs. But each reckoning with the truth of abuse, each telling, lightens the pain for the survivor and lessens the generational load. After all, secrets are only powerful in the dark. The trick is to carry a lamp into that velvety room, and turn it on.