Why are you moving so far away?

That was a question family members kept asking hubby and me, in the early years of our marriage, as we moved, and kept on moving, to Newfoundland, to Labrador, to the Madawaska Valley, to Northwestern Ontario. By “so far away” they meant so far from the golden horseshoe, from the 401 and all its pit-stops, Autotown, (de)Forest City, Steeltown, and the Megapolis one longs to go T-O.

The movers said it would take them a week to deliver our stuff to Thunder Bay. You’d think we were moving to another country.

Yet, it was a long, long drive to our new home. Twenty hours over two days. Urban density gave way to sprawl, to industrial wasteland, to farmland, to north-town Ontario. Main streets nestled between swaths of bush, which stretched longer and longer as we drove further and further north and west, till we were nothing but a little grey beetle crawling through a vast forest beside a great sea.

We refilled for gas whenever opportunity arose, road signs warning us not to wait until nearly empty. A little path behind a gas station took us to a riverbank where we watched a blue heron spear frogs from the water. When we stopped for a pee along a burnt-over patch of forest, a moose cow and her calves looked up from their blueberry browsing to study us with as much curiosity as we them.

Why did we want to go to such a remote location? And was it really remote? After all, we arrived at a hub with plenty of stoplights, all the major fast food restaurants and department stores, including two Canadian Tires (one for each of the twin towns that amalgamated into one city), a multitude of hockey arenas, and a college and a university (either of which we could readily bike to). What more could we want?

What does remote mean?

The most common meaning of remote is “far away.”

But far away from what? In Thunder Bay, the word “remote” is usually heard in a newscast or weather report in reference to communities in the upper half of the province: end-of-road communities or First Nation communities without road access, whose residents visit Thunder Bay to access health services, secondary education, and box-store shopping. We were not at all remote in that sense. We were surrounded by people and stores and schools, although not by extended family. Since it is generally recognized that it is much further to go from a centre than to it, we’d regularly take trips to visit our families. At the end of a visit, my mother-in-law would stand at the door, waving and crying. Why must we live so far away?

Yet, I wasn’t the only person in our families to move “far away.” My own parents, retiring at their earliest possible opportunity, went to live at their summer cabin. They became the most westerly residents on Manitoulin Island, on a bush acreage they called Far Point. Why did they go there? An eight-hour drive to Toronto, a thirty-minute walk to the nearest neighbours, an hour drive to a grocery store. Well, they wanted to be away from it all, away from the city they had always hated, with its traffic and crowds, parking restrictions, parking tickets. They wanted an unregulated township, fewer constraints. They wanted to be alone to do their own thing.

“When we want culture, we eat yogourt,” my parents would joke. “Cultivation is pushing a rototiller down a garden row.” On the outstretched arms of a scarecrow, my parents set a radio at an unstable setting so that the stuffed head would erratically erupt in song, news, or weather reports. And they lined their garden with electric fencing to keep out the more insouciant marauders.

They couldn’t come to visit us, because we lived much too far away.

To be remote can also mean to be emotionally distant.

Physical distance can offer self-protection from relational difficulties. In my high-voltage family, we needed space from each other. Yet we craved connection, too.

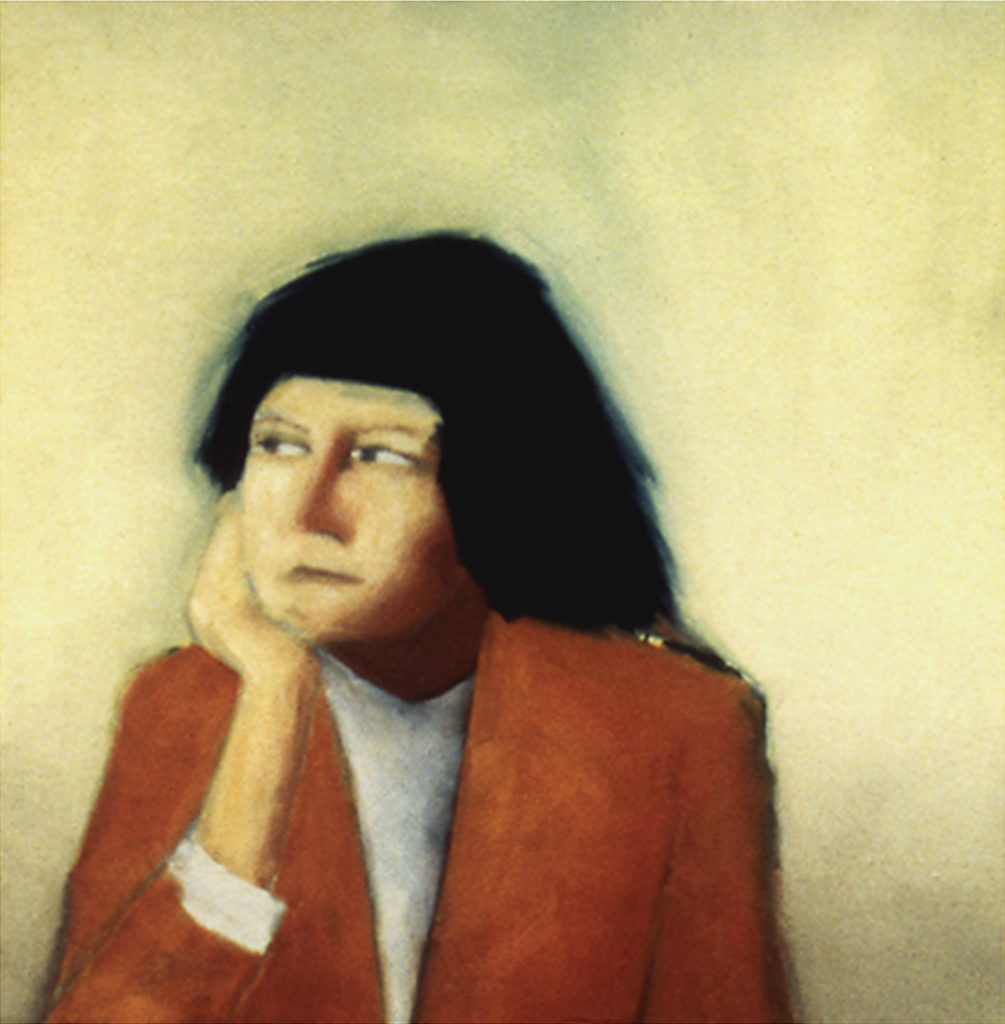

Untitled by Jacqueline Staikos

On my very first day in Thunder Bay, waiting at a traffic light, someone in the next lane signalled me to roll down my window. “Something’s trailing from your side door,” she advised. This struck me as a small-town, care-for-your-neighbour kind of thing, something that didn’t often happen in the big cities where I’d lived. Growing up in Toronto, everyone seemed remote. Big city ethos: Don’t show me your feelings and I won’t show you mine. Once I thought I saw my Grade 8 teacher on the subway, and I stared repeatedly, as much as urban-ity would allow, but I didn’t dare say anything. Growing up in this big city, I never knew who’d be in my class one year to the next; some may have moved to another planet as I never saw them again.

So be it.

I live, now, in a hilltop neighbourhood. If I stroll to the perimeters of the hill, I can see to the borders of the city and beyond: Lake Superior (Gichigami) to the east, the Nor’Wester Mountains (Animikii-wajiw) to the south, and to the north and west, trees, hills, trees.

Roses are difficult here. But chipmunks, ravens, and one lone snowshoe hare enjoy my vegetable garden: rhubarb, chives, zucchini—just the hardy stuff. My vegetables have to be tough because my unweeded perennial beds have gradually transformed our yard into boreal forest.

Many rivers wind their way through the city on route to the great lake. Every spring melt, I see anglers, bankside or waded in, trying to catch a spawning trout. Bears will also follow this trail to fish, or to the city’s intriguing odours. Letters to the paper remind us that a recently closed outdoor pool was originally built as a safer option to the city’s unguarded rivers. National journalists tell even darker stories about the waterways.

Thunder Bay reminds me that “far away” is still a “here” and “here” is always an “us.”

The word remote comes from the Latin verb removere, from which we also get the verb “remove.” Used reflexively, it suggests a self-willed action.

To remove oneself is a choice. My husband and I chose to move here. And now, two of our children, grown up and graduated from local post-secondary institutions, have removed themselves from this northern city, with their spouses and families, for jobs not found around here. When we get together, we gather in a big circle around a table and eat and drink and chat and laugh and argue. We philosophize about human rights, freedoms, oppressions, privileges, responsibilities, the government and the individual. Often, we don’t agree. Between visits, video technology keeps us connected. But a video cannot give the weight of baby on hip; neither tennis ball nor cake can be passed through a computer screen, even though we pretend: “On the count of three, let’s all blow out the candles.” So, at the end of a visit, I’m the one at the door now, tearfully waving goodbye.

Remote can also be a transitive verb. Though rarely used this way, it refers to the moving of something or someone to something or someone else. The action is willed by the mover.

For some, re-motion or re-moval is not a choice. I think about my Slavic grandmother, mentally unwell, deported under Canada’s War Measures Act as an undesirable citizen. I think about my father, renamed, rebirthed, reparented. I think about my husband’s Irish great-grandfather, forced from family and land by famine. I think about all my great remote grandmothers, whose names are lost to me, filles du roi, voyageur wives, whose children were lost to them, for the sake of assimilation or education or societal expectation of betterment.

We all experience “remote” in some way or other. To be remote is to be far away from others. If those others are your kin, remoting is a leave-taking. We all have a time of standing sadly at the door.

Listen to Holly Tsun Haggarty read “On Being Remote (& Saying Good-Bye).”