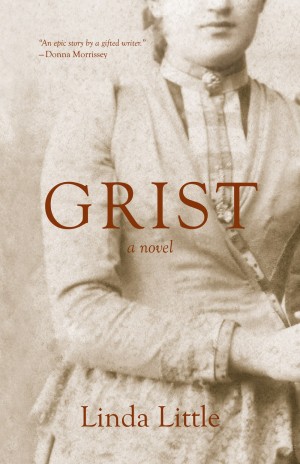

Linda Little’s latest novel, Grist, examines motherhood, gender roles, and hard work through the character of Penelope, a women left alone to run a mill in nineteenth-century rural Nova Scotia. Grist has received fabulous reviews. Understorey Magazine spoke with Linda about her novel and her work.

Understorey Magazine: There are autobiographical elements in Grist. You once worked in the Balmoral Grist Mill near Tatamagouche, for instance. Are there parts of you in Penelope too?

Linda Little: Certainly, my working at the grist mill was the fundamental inspiration for the novel. I love the mill and it was the springboard for the story. As for Penelope, I really didn’t draw much on my own experience or character. It’s hard to know how any of us would now respond to, and manage under, the circumstances that nineteenth-century women experienced as the norm. Penelope did what she could with the options and opportunities that arose—which is what we all strive to do, I suppose.

Understorey Magazine: You won the Thomas Raddall Atlantic Fiction Award for Scotch River in 2007. How did winning this prize influence your writing career?

Linda Little: It was wonderful to win that award. It is always a great thrill to have a novel receive extra attention. (And then there’s the money….) Having said this, it is important to remember that an award does not change a book. A novel is just as important/moving/affective to its readers before or after, with or without an award. Who wins an award depends on who sits on the jury. The great thing about an award is the chance to gain new readers. Yes, an award looks great on a resume but really, not many people ever need to see my resume these days.

Understorey Magazine: What keeps you writing, especially through those difficult days when the words don’t flow?

Linda Little: Writers need to bring their own motivations to their work. Just because a person is sitting in front of their computer does not mean they will capture something on the screen. But if you’re not sitting there, it is guaranteed you won’t! Writing Grist was a long and difficult process for me. I had to rewrite the book several times from different points of view, and by the end of the process my energy was just about spent. For my two earlier books and in the first few years of writing Grist the stories themselves carried me. When the going gets tough though, I think sheer naked determination is probably your best bet. There’s nothing fancy about it. I imagination the process has strong parallels to raising teenagers—it’s not fun any more but you can’t just stop. “In for a penny, in for a pound,” as the old saying goes. Just believe in the absence of other options.

Excerpt from Grist

Cold closed in as we headed further down through December. Listlessness tugged at me. My days were peppered with bouts of feeling morose and ill. As Christmastime approached I brought an armful of evergreen boughs into the house and urged myself towards some small effort for the season though I knew from experience that Ewan would work as usual on Christmas Day. I visited Nettle for the few supplies I would need to make the Christmas pudding which would elicit no comment from him, one way or the other.

On Christmas morning I woke to a soft snowfall. Ewan had already left for the mill as usual. I pulled on my coat and boots and stepped out into the fresh, white hush and turned my face to the sky. The world was magnificent. I only needed to open my arms to receive its blessings. Buoyed, and thankful that I had made the small efforts I had, I set to my chores in anticipation. Then I packed up my gingerbread creation and bore it triumphantly up to Browns’ where I knew there would be Christmas cheer in abundance.

Indeed the family enveloped me the moment I entered. The children clamoured to show me the treasures Santa Claus had left them.

“Look, Mrs. MacLaughlin—an orange and a stick of candy! And the whole of it’s for me!”

“See mine, Mrs. MacLaughlin?”

“What have you got in your package, Mrs. MacLaughlin?” young Peter asked.

“I’ve brought a surprise. Shall we set it out here on the table where everyone can have a look?”

The children crowded around as I unveiled the little house with its candy-shingled roof and walls and its gumdropped laneway. I had made six gingerbread figures—one for each child—cavorting in the egg-white icing snow.

“Look at the windows!” cried Harriet. “They’re like real glass, but candy!”

“Look at the peppermints!”

“This gingerbread boy is me! See, Mama, he’s got a snowball!”

When I looked up Abby was staring at me with the most bewildered look on her face. She smiled then, of course, and gushed about the house, but I had caught her out. I felt my social self peel away, outwardly listening to the children’s questions and exclamations but underneath an awkward ache tugged me away from them.

Later, with the children sent outside to play, Abby turned to me. She cupped my chin with her hand and peered intently into my face. “Penelope, I believe you have that glow. Am I right? When did you have your last…?”

Answering her whispered questions, I pressed my palms to my womb. Yes. I had been so foolish with fussing over my troubles that I had missed the very gifts set before me.

“Yes,” Abby nodded. “There is a glow, I’m sure of it.”

I walked slowly and carefully down to the mill feeling more certain with each step. I found him by the fodder stone.

“Ewan,” I whispered, setting my hand on his shoulder, “I think we may be blessed. A child.”

Ewan cocked his head, stared at my abdomen. “Ah, your extra labour when I was gone. This is your reward.”

I caught a merry laugh as it bubbled up, caught it just in time and contained it in a smile. Had he been a different sort of man I would have teased him that a man’s absence from his wife is seldom rewarded in this way. Instead I leaned over and kissed his cheek.

I sang at my work and prayed and worked and sang some more. After all my waiting and troubles and disappointments, I felt so certain, so strong. On Sundays I visited with Abby revelling in her little ones as proof of how it would be, splashing optimism everywhere, painting the world with certainty. Abby gave me little dresses as patterns for the wee gowns I stitched and decorated. Mrs. Cunningham deduced or heard the news of my condition. When I met her on the road on my way back from Nettle’s she shot a doubtful frown over my body and advised that after this long time I shouldn’t get my hopes up.

On a winter day like so many of the days that linked dramatic weather—a seasonal day wrapped in batting, an everyday day—I was hauling water to the barn, breaking the ice on the pails and topping them up with fresh water from the well. The barn was cozy with the warm redolence of animal breath and I took my time with the beasts, stroking Billy’s nose and Pride’s too when she nuzzled over, jealous, patting the flanks of the cows. I had a bred heifer that would freshen in the spring and each day I ran my hands over her and down her hind legs, across her udder, preparing her with my smell and touch, feeding a handful of molasses oats with my ministrations. I carried armloads of hay out to the loafing shed where the sheep greeted my benevolence with bleats of praise. I had just given the horses their winter rations from the oat bag when I felt it. A nudge, a shift. If it had been a sound it would have been a rustle. Involuntarily I looked down at the front of my coat the way one might turn towards a tap on the shoulder. Beneath my palm, beneath a layer of stretched skin and a shallow dome of flesh, a human child had moved. No longer me, now a person in its own right, a baby swaddled by my body, of me but not me. My child, Ewan’s child, whose arms and legs were guided by its own separate little heart and mind. Such a flowering of pure love enveloped me I could barely breathe. “Again, my dear one,” I whispered, coaxing, now clutching my womb with both hands. I waited, my heart as broad and steadfast as the great gentle horses beside me. It came again—a flutter this time. I wept with wonder of it. The quickening.

From that day forward I never sat or stood or moved without thought of the baby I carried beneath my heart. I carried the babe through the cold of February, the ice of March, the inconstancy of April, the dawn of spring and into the fullness of summer. When the water ran low Ewan returned to Curry Point for a fortnight. I hardly noticed his absence. I carried my bundle as it grew and kicked, speaking to me as I spoke to it.

Our baby daughter came with the summer daisies, with all the hope and joy that happy flower brings. Ewan smiled and held the child, his disappointment at her sex soothed by her vibrant health. I felt our lives were beginning again, that everything up to this point had been a long meandering opening chapter; necessary detail perhaps, but now the story would begin.

“Our next will be a boy,” I promised.

“Aye,” he said.