Even though my passport says I am Canadian, my body—my tanned skin and my dark hair—sometimes suggests otherwise. When I was nineteen, I left my home in Toronto for a five-week French immersion program in Chicoutimi, a lovely little town in northern Quebec. When I first met my host family, my host mother Marie-Paul asked me, “D’ou viens-tu?” or Where do you come from?

“Je viens de Toronto,” I replied.

“Non, non, quel pays?” Which country, she asked, shaking her head.

“Oh. Mes parents viennent de la Guyane.”

“La Guyane Francaise?” Both of my host parents laughed.

I laughed too the first time, but when this joke was endlessly repeated, it ceased to be funny. When you are told the same thing over and over again, it can become part of you. I came to think of myself as an outsider in Canada, even though I was born and raised in Toronto.

And yet, I don’t feel a strong connection to Guyanese culture—in my home in Toronto or the “homeland” of Guyana—either. Most of my high school was Indo-Carribean or Indian but the stereotypical Guyanese girl in Toronto is rowdy, likes to have a good time, loves to dance, drink and fête until the sun comes up. They can be stubborn and mouth off. Obviously, this doesn’t apply to every West Indian, but it is the image that’s perpetuated. So my little sister loves to call me white-washed. She cites my disdain for heavy drinking, the fact that I don’t go crazy on the dance floor and my absolute aggravation when she blasts chutney music from her bedroom. According to the stereotype, I should like these things. According to my sister, that fact that I don’t makes me white.

So I’m not quite Canadian and not quite Guyanese-Canadian. Where does that leave me?

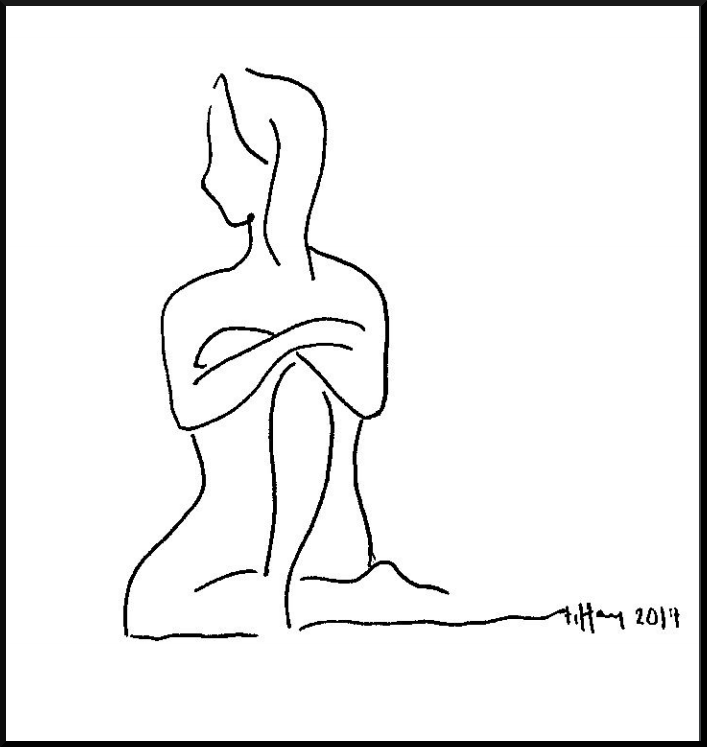

Waiting by Tiffany Rambali

I have only two memories from my first voyage to Guyana, a trip that I made with my family when I was six years old. The first is of lying in a hammock when a frog jumped onto the cement underneath me. It settled in, relaxing. Its bulbous eyes seemed to pop out of its skull, black lines painted across its slimy green skin like veins. I was amazed that a frog could live in such a hot country. I could just imagine it melting into green slime until it was nothing but a cartoony pair of eyes.

The second memory is of the night we spent in my “grandma’s” house. She was not actually my grandmother; I’m not sure how we were related. That’s a funny thing about West Indians: everyone older than you is an aunty, uncle, grandma or grandpa. At this grandma’s house, I slept underneath a mosquito net in a room with the window open. Even at night, the humidity was suffocating, and even with the net I could feel my skin starting to itch. I tossed and turned until I finally fell asleep.

What I don’t remember from my first visit to Guyana was what struck me most on my second visit when I was eighteen. That time, we stayed with my mother’s cousin. All I could see were divisions, that Guyana was not one people, one race or one class: The fancy community where my relatives lived, the houses all like mansions with their own security guards and gates, and the shacks lined up in the village five minutes away. The names of the village and streets in French, English and Dutch, all remnants of the colonizers who left their footprints. The congregation of black people and Indian people in the malls and the way they eyed each other with apprehension. The domestic dogs, strong and fearsome like regal guards of a palace, and the strays with skin adhering to their bones, passed out in the heat.

There were no stereotypical Guyanese girls here. Yet, everywhere we went during that trip, I still felt like an outsider. In Guyana, everyone can tell you are from “out-away” by your clothes, your accent and for the simple fact that they don’t know you in a country where everyone knows everyone.

One night I was chatting with my cousin Kiesha. We were identical in age but I already assumed we would be different. She was Guyanese, after all, and I was…? I still wasn’t sure.

“I don’t really like to drink,” I told Kiesha. “I might have one or two, but that’s it.” I expected Kiesha to scoff at me, to laugh at my inexperience and “whiteness.”

“Oh, you’re like me,” she said. “I don’t like going out and drinking too much.”

You’re like me…. A little phrase that stuck with me. Kiesha and I were actually very much alike. We were both studious, partied in moderation and we both enjoyed a healthy number of extracurricular councils at school. We were even physically alike, our dark hair shoulder length and slightly frizzy, our bodies petite but slightly curvy—young women who could fit in each other’s clothes. How could someone so far from home be closer to me than the girls in my school?

I had always disassociated myself from post-colonial and diasporic stories. They seemed to be about the mixed-race child trying to make sense of their mom and dad’s sides of the family. Or they told of the immigrant in shock, of trying to pick up a new language in a new land. All of the characters, sometimes fictional and sometimes real, were literally outsiders—born outside their resident country. But the truth is, the children of immigrants are sometimes just as lost. Immigrant families flock together in niche neighbourhoods in select cities and their children try to navigate the culture of their community within the larger Canadian culture, the two constantly at odds—as they often are in me.

I had always felt stuck in that jarring gap between Canadian and Guyanese. It sometimes felt like a gorge, dark and lonely, any hint of a bridge long eroded away. But as I get older, as my known world expands, I’m learning to find myself in that in-between space and build my own connections across this gap. I’m starting to write my own story.

#

Related reading: Two poems by Ayesha Chatterjee