Zoe had burnt her French toast and flung it in the garbage. She’d made a wrap, too, but the eggs had not set. She’d slammed the wrap on the counter and disgusting blobs of egg white now clung to the sides of the toaster. Finally, she had settled for half a piece of toast and peanut butter. Susan knew Zoe hated toast.

“We could make biscuits together,” Susan said, purposely keeping her voice soft and steady.

Breakfast had been disastrous, but baking was the only activity that soothed Zoe and gave her some sense of accomplishment. Susan pulled out the cookbook and copied the directions onto a piece of paper, outlining the steps in a way that would be easy to follow.

Find baking tray.

Put all ingredients on kitchen table.

Get measuring cups….

“Okay honey, take this three-quarter-cup measure. Pour in the buttermilk. Good. Now add that to the dry ingredients.”

Susan watched as Zoe poured the buttermilk, then quickly repeated the step twice.

“Okay… so why did you add three?”

“You said three cups.”

“No, honey, you misunderstood. I said fill the three-quarter cup.”

Zoe sprang up, fired the cup across the room, and strode out of the kitchen, shoving and overturning a chair in her path. Susan stood still and silent. Down the hall a door banged.

Susan dropped her shoulders and took three slow, deep breaths. In for three. Hold for six. Out for six.

Zoe was thirty-five, no longer a baby, yet she’d lost so much in the last sixteen years: the ability to think things through, to follow directions, to control emotions. She grew frustrated by her difficulty figuring anything out. But the more Zoe overreacted the quieter her mother would become. Susan had long ago learned that explaining, negotiating, or arguing didn’t work with someone whose brain struggled so hard.

One more long, slow deep breath then Susan scooped some of the buttermilk out of the bowl and finished making the biscuits, all the while listening for the sound of things being thrown or broken. Nothing. That was progress. With one ear still open, she continued to clear up the mess. Susan knew Zoe needed time and space, things the hospital had never offered. The staff had always seemed too quick to call security, man-handle, inject, lock up.

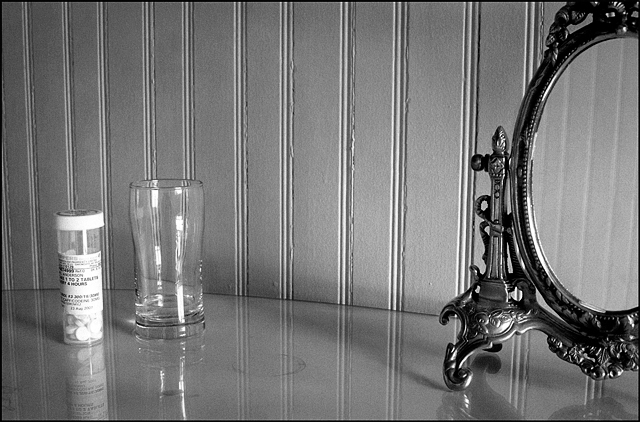

All was quiet. Susan walked softly down the hall to the living room. Zoe was on the couch, feet tucked under her, a pad of paper on her lap, and a tube of bright blue acrylic paint clutched in her fist. A dozen books, more tubes of paint, papers, crystals, bottles of essential oils, and bits of craft materials littered the coffee table in front of her. A plastic pill container with the day’s ration of anti-psychotics and anti-depressants sat beside a glass of water.

Zoe aimed the blue tube at the paper and squeezed hard trying to dislodge the dried paint that had sealed the opening after the cap disappeared. The tube split and the paint shot onto the floor, her hands, her clothes, her new pillow. Zoe sat frozen, bright blue streaming down her wrist and dripping onto her lap. Susan reached for the roll of paper towel under the coffee table, then gently took the tube from Zoe and wiped her daughter’s hand.

“I’ll just get some wet cloths,” Susan said.

She wiped up the globs of paint as best she could. Zoe said nothing. She lay curled up on the couch, a throw over her head. It was a huge improvement over last year when Zoe had overturned the coffee table and thrown water glasses. The year before that the glasses had been aimed at Susan.

“Good for you, Zoe, for staying cool. I know it’s frustrating.”

No response.

“The biscuits are almost done. Would you like some milk?”

Silence.

Susan arranged the biscuits and jelly and thought about the last few days. Weeks. Exhausting, yes, but nothing like it had been. Despite the mess in the kitchen and living room, the last hour could be counted a success for both of them. Susan had not raised her voice. She had not chattered endlessly, and Zoe had settled in spite of the paint and failed kitchen experiments.

“Hey, I think we both did pretty good getting through the last few minutes.” Susan moved a few things from the coffee table to the floor to make room for the biscuits.

“Why are you so nice to me?” Zoe was now sitting up, the throw slung over her feet.

“Well, I know you’re frustrated. And I do think you did a good job settling down. I have no reason to not be nice. And … I love you. No matter what.”

Susan sat down on the couch. Zoe leaned into her mother. They sat quietly, unaware of the passing of time. It was the moment that mattered. And later, if Zoe wanted to talk she would listen and say little. It would be a few more hours before Susan would allow herself to cry in the shower. And then, sitting on the bathroom floor, she’d pull herself together, one slow deep breath at a time. Baby steps.