Does motherhood stifle creativity? Can mothers be successful authors?

Do we even need to ask these questions? After all, it’s 2015.

But just two years ago, The Atlantic published this headline: “The Secret to Being Both a Successful Writer and a Mother: Have Just One Kid.” The title was meant to provoke. The author, Lauren Sandler, did not make this sweeping claim. Not quite. She was looking for literary role models and found several who, like her, have only one child.

Nonetheless, the essay re-ignited smouldering debate about motherhood, publishing and social policy.

Zadie Smith, award-winning author and mother of two, responded to the article:

The idea that motherhood is inherently somehow a threat to creativity is just absurd. What IS a threat to all women’s freedoms is the issue of time….”

Jane Smiley, Anakana Schofield, Aimee Phan and many other women and men, writers and non-writers, weighed in. Most noted that workplace success depends less on the existence or number of children than on how parenting time and duties are shared.

There is good reason for such ongoing debate. In heterosexual couples, women still shoulder an unequal amount of childcare and household responsibility. At the same time, in almost forty percent of households with children (in the US, at least), women are the primary or sole wage earner. Women are very busy. It’s perhaps unsurprising, then, that compared to men, women win fewer literary awards, publish fewer books and have fewer books reviewed. Even books about women are less likely to win prizes.

So while we work for more equitable social policies and a more diverse publishing industry, we need to keep asking questions.

And we have.

Understorey Magazine invited eight Canadian authors who are also mothers (see their biographies below) to share experiences and advice, mother-writer to mother-writer. Their responses were diverse, as you might expect. But issue of time was front and centre:

Motherhood and writing. Eek. I suspect the largest “hindrance” is the way motherhood distracts and divides your time and attention. I am forced to make choices between the kids and the work, sometimes work wins, sometimes the kids win. But even when I’m writing, my head is never one hundred percent there. I have random thoughts about the kids all day, every day.

— Natalie Corbett Sampson

I don’t know if having children stifles creativity so much as it siphons time. I think many female writers who are mothers fear how children will interrupt their writing timeline: “I must release my second novel within three years or I will lose momentum or become irrelevant.”

— Ali Bryan

Women writers often also work as teachers and mentors, a role others often see as maternal. Its demands are huge, and women, especially, are expected to be selfless and giving. The time “between the cracks,” the shadow work, both paid and unpaid, can consume us unless we’re careful. Whether it’s our children or our students, women writers have to negotiate daily the means to protect our writing time and meet others’ needs.

— Lorri Neilsen Glenn

I would like to wave a wand and make it acceptable for women to proclaim not only, “I’m utterly uninterested in bearing and raising children ever,” but also, “I’m all-consumed by raising children and I don’t feel like writing now.” That both these statements remain taboo means that women in the former situation have to justify choosing art over babies, and those in the latter find themselves impossibly stretched, so that it begins to appear that writing and motherhood are incompatible.

— Kerry Clare

Of course, it’s not just mothers or writers who are clamouring for more time. But mothers are particularly stretched and writing, for most, is not a job that pays the bills. Writing must be squeezed in among other commitments—and mothers have a lot of commitments.

This is something guides to writing and publishing rarely discuss. In fact, general advice on the writing life often stresses the benefits of solitude and uninterrupted thought, precisely what many mothers—especially new mothers—lack.

Still, mothers write books. Good books. Great books.

Author Joanne Harris notes, “No man in publishing is ever described as ‘juggling’ anything.” Successful women, however, are constantly asked, “How do you do it?” And we still need to know.

We asked mother-authors what they might add to a guidebook on writing.

I think being at the heart of this whirring, exciting dynamo (two four-year-old boys, two careers each for my wife and me, and extended family on two continents) has unlocked a level of directness and emotion that I couldn’t access in my writing before. It is a gift—though I don’t want to romanticise it too much. Sometimes you just need to finish your draft and the dishes are piled and someone has cut his knee and there is a stack of papers to mark and the dog needs out. Yes, that happens. So it has made me hard-nosed about my writing time. There is none of this getting into the mood and waiting for inspiration to strike. If I have half an hour at the bus stop, the notebook is out. If I am sitting near a giant jungle gym with my boys while two hundred kids release their pent-up howls, well, I put on my earphones and keep writing. So for advice, I would say try to be tough and vulnerable at the same time. You have to let people around you know that your writing is key to your happiness. Let them have the chance to help out.

— Natalie Meisner

My routine has been different every year of my children’s life, when i was married and as a single mother. Our daily and weekly schedule changes over time. And that one truth might give the most relief to someone struggling right now. It always changes. And we have the power to make it work better, even if the only thing that shifts is time itself. Can you get up one hour earlier in the morning to write? Can the children spend time with someone else for two hours twice a week? Do you have a writing space and are they old enough to respect that space and leave you to it? Can you incorporate their reading or writing into yours? Can you create a writing club? Can you write little notes all week, flashes of ideas, and save them up for a weekend morning while your family or kids are busy? Or can you stay later at work once or twice a week and switch to writing at the end of the day? You have to take time to reflect and make a new plan if something isn’t working. Because it can work.

— Shalan Joudry

Last night I attended a reading by a poet who claimed to have spent five months doing nothing but work on one poem. My first thought was, What a luxury. But the more I considered it, the more horrific that notion seemed. I am prolific because I don’t have five months to write a single poem. I’ve written entire novels in five months because I am forced to make time. I wrote the final draft of my first novel with one hand while I held my breastfeeding infant in the other. The chaos of home life and parenting can also influence the writing. I seldom write long, lyrical passages of description because I don’t have time for that. My chapters are short, my pace quick, likely an influence of only being able to squeeze in a few hours at 5:00 am before people start wandering down from upstairs looking for breakfast.

— Ali Bryan

If you really want to do it, you can make it work. How? Read while the baby sleeps. And eats. When babies are small, you can write lying down with a laptop on your knees while the baby naps on your chest. Compose stories in your head while you’re out pushing your stroller. Learn to zone out your children and the world around you so that you can write a novel while your older daughter watches Annie and the baby naps. Never do housework or errands on your own time—bring the children along to the post office and call it an education. Don’t be too much fun that they’re happy to play without you. Always have a book in your bag. Don’t volunteer to be classroom parent. Ask a lot or enough of your partner. Accept that sometimes your workday will start at 9 pm.

— Kerry Clare

A time and space of one’s own is very important. Once or twice a week, every day, an hour or two at a time, even a full day—but your own, discrete, private, personal, alone time. For some people, particularly single mothers, this will often mean night time, after kids go to bed (if exhaustion will allow for ideas) or while they’re in school (if you are not working elsewhere). If there is a partner, this is the job of a partner, to help care for children and to allow for the work you need to do to get done. I’ve enjoyed sharing time and space with other writers, each writing, quietly, outside the home, together. Perhaps we need a pooled space for women, with childcare arranged, so that we can write. Wouldn’t that be amazing?

— Alice Burdick

I kept a notebook in my pocket, carried scraps of poems in my head, escaped for a few days’ retreat every few months where someone else made meals and let me hide in a room or walk outdoors muttering to myself. At meals, I had that faraway stare so common to artists, so grateful I was to be lost in words, to have hours on my own. Hell, I’d gladly have eaten a week of liver and onions for that gift of time. — Lorri Neilsen Glenn

So there are personal and practical ways for busy women to find time to write and publish. And there are certainly social and political ways to allow mothers more time to pursue work beyond childcare. But there are also philosophical ways to bridge that gap between the reality of life with kids and the desire, sometimes need, to write—and to address the entrenched fear that life’s interruptions will stifle larger literary goals.

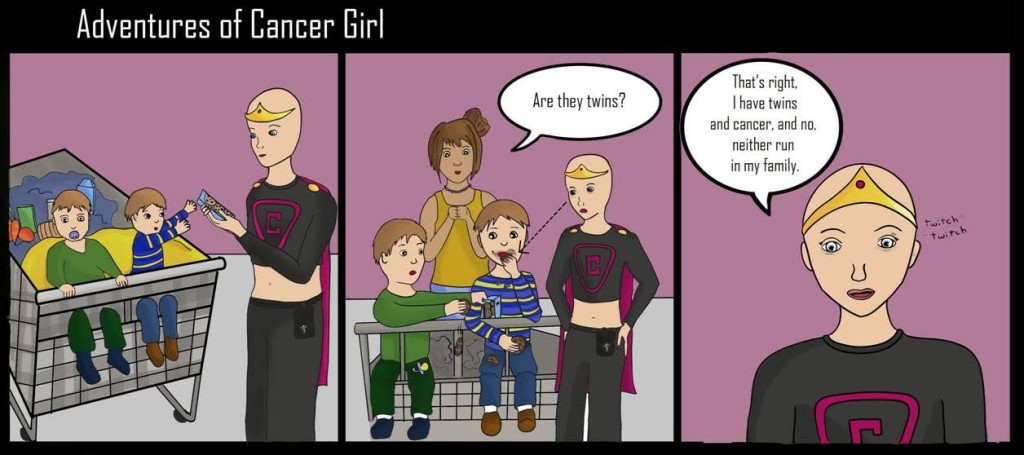

In her wonderful collection 100 Essays I Did Not Have Time to Write, Sarah Ruhl, award-winning playwright and mother of three, brings her motherhood straight into the pages of a book on theatre. Sentences are dropped because a son needs to poop or suddenly usurps the keyboard. And then the sentences—and the insight, humour and wisdom of a professional career—are picked up again. Ruhl says that after having twins she thought her writing career was over, “annihilated.” And then she had a thought:

All right, then, annihilate me; that other self was a fiction anyhow. And then I could breathe. I could investigate the pauses. I found that life intruding on writing was, in fact, life.

The authors we spoke with had more to say on this point than any other: Acknowledge, examine, sometimes even embrace the pauses, whether they last a few seconds or a few years. Blur the line between life and art and then move on to live and create.

I don’t think the model of the committed writer is realistic for many people right now. Only a very few writers can support themselves so most have distractions of other jobs and roles. Shutting the world and your experience out in a “no diversion” and “no intrusion” approach leaves you open to missing things that can be shaped into stories. I absolutely think my children contribute a huge amount to who I am as a writer and professional. It’s cliché, but they teach me and push me every day to be a better person as a whole, and that feeds into the way I interact with my clients at work and develop my writing/characters/stories.

— Natalie Corbett Sampson

If we are to say, “Yes, we struggle with work and motherhood,” then let us say it in a new way. When i think about the kinds of stories i love best it’s the ones that are specific, unique and hauntingly beautiful in their own being. I find that we write those interesting characters and stories after we have first pulled off the outer layers. Yes, as mothers we feel as though we’re neglecting our children to write or do something for ourselves. Yes, ok. Write that down first to get it out. Write it on paper, your computer, your journal, or say it out loud. Get it off your conscience. In our culture, we sometimes call that letting go of it in the sacred fire. It’s also about forgiving ourselves. Then we can get to the next layer of identity and ideas and it gets more interesting or specific. We take another turn around the circle, like a sharing circle, and maybe we share more, something that has even more depth and truth. We live these everyday. They are gorgeous human stories. Like when our child responds to an issue with such clarity or humour that we undo something in ourselves. Give that opportunity to your character and plot.

— Shalan Joudry

Although there are some instances where writers are contractually obligated to release material within a specified timeline, most of our timelines are perceived, self-imposed or merely recommended. The reality is that even the most successful writers don’t have readers who are sitting around desperate to read their work. No one really cares about your book. You are not the world’s one designated writer, so the book can wait. I remind myself of this often when my need to write outweighs my desire to parent. I’ve learned to pick parenting. A tea party or a baseball draft means more to a child in that moment than the book will ever mean to a stranger. And as cliché as it sounds, they grow fast. I have two kids in elementary and one in preschool. I’ve joked that by the time all three are in school full-time I won’t be able to write at all.

— Ali Bryan

Poet Lucille Clifton said, “Why do you think my poems are so short?” With six children, she had a houseful of activity. Carol Shields, the much-loved novelist, had five children and managed to steal time to write stories longhand at the kitchen table. Are these women superhuman, or can the rest of us accomplish this? I’m not sure, but there’s something in there about motivation, about an urgent need to express ourselves, about loving and valuing the work as much as we love and value our families.

— Lorri Neilsen Glenn

In my early, fiery days of deciding to be a writer, it felt like the odds were indeed stacked against any young Canadian making a living in the arts—let alone a woman, let alone a lesbian from a working class background in a small town in southwest Nova Scotia. During those days, I inhaled the work and also studied the lives of solitary literary lionesses like Virginia Woolf and Elizabeth Bishop. I internalized, without meaning to, the idea that you needed to stay unencumbered and light on your feet. Family, the running of a household and babies, especially, seemed antithetical to the hours of reading and practice needed to truly hone a craft. For nearly a decade, I kept myself quite free of such “impediments” until it became radically apparent that attachment—that is really what life is all about! How could I have ever dreamed that you could make silos in this way? Writing, love, ties, attachment, they are all wound up in the knotty secret heart of a writer.

— Natalie Meisner

This will sound odd, but having dealt with trauma from a young age, I’ve become used to the idea that writing can wait and life can take centre stage. And yes, the words will come back. So at the very outset of motherhood, taking care of an infant, exhaustion may take over, the body takes over. But the mind in the meantime works away, the words to come. If you write, then writing is a part of your life, and you can let other parts of your life nourish it.

— Alice Burdick

Know too that motherhood becomes less devouring as the children grow. If there isn’t time for writing now, one day there will be. Take it easy on yourself. Concentrate on the moment at hand. Take notes.

— Kerry Clare

The experiences generously shared here are neither definitive or representative. How could they be? But in offering a glimpse of different writers, mothers and lives, we hope to keep the conversation—and the writing—alive. As Shalan Joudry says:

What helped me was talking with other women about writing. We’re all so different but it felt good to swap stories and see how our different lifestyles affect our writing routine.

In this spirit of sharing stories, we invite you to join in. Post your thoughts, advice, experiences and comments below or send them to

Understorey Magazine.

We give the last words of this essay to Sylvia D. Hamilton:

Believe in yourself. You have to believe in you, otherwise why should anyone else? Douse the rising self-doubt. Tip the scale inward. Practice trusting in yourself.

With many thanks….

Ali Bryan is the author of Roost (Freehand Books), the 2014 pick for One Book Nova Scotia. She is at work on a second novel.

Alice Burdick is the author of three collections of poetry and co-owner of Lexicon Books. Her fourth poetry collection, Book of Short Sentences, will be published by Mansfield Press in 2016.

Kerry Clare is editor of The M Word: Conversations About Motherhood (Goose Lane Editions). Her first novel, Mitzi Bytes, will be published in 2017.

Lorri Neilsen Glenn is the author of six books, including Untying the Apron: Daughters Remember Mothers of the 1950s (Guernica Editions). She was Poet Laureate of Halifax from 2005-2009 and currently teaches at Mount St. Vincent University.

Natalie Corbett Sampson is the author of Game Plan and Aptitude (Fierce Ink Books). Her third novel, It Should Have Been a #GoodDay, is forthcoming in 2016.

Natalie Meisner is a writer from Nova Scotia and Professor of English at Mount Royal University in Calgary. Her first work of nonfiction, Double Pregnant: Two Lesbians Make a Family (Fernwood Publishing), was a finalist in the Atlantic Book Awards.

Shalan Joudry is the author of Generations Re-merging, a collections of poems (Gaspereau Press). She is also a performance artist, storyteller, cultural interpreter and ecologist at the Bear River First Nation in Nova Scotia.

Sylvia D. Hamilton is a writer, award-winning filmmaker and professor in the School of Journalism at the University of King’s College in Halifax. Her poetry collection And I Alone Escaped to Tell You (Gaspereau Press) was nominated for an East Coast Literary Award.

*

Understorey Magazine is a project of the Second Story Women’s Centre and a registered charity. If you like what you see here, please share with friends and consider making a donation. Thank you.