Dear Africa,

I want to apologize. I had no reason to abandon you. I had no reason to push you away. I wanted to hide from you. I wanted to pretend that you didn’t exist. But I know you have always been in my blood. Rushing, pumping, flowing.

As a child, I remember enjoying the uniqueness of my family. My mother was an Afrocentric, biracial woman with a strong desire to expose her children to diversity and equal opportunities. My father was a tall, dark Angolan man who was funny and spoke to everyone with a natural grace and fluidity. Our home was filled with beautiful African décor. Our dinners consisted of traditional Angolan foods that stuck to our bellies. The rhythmic sounds of Semba and Kizomba bounced off our walls and I would bask in its comfort. Occasionally, we would get together for parties with other Angolan families in Toronto. There was laughter. Dancing. Music. Food. This was one of my first experiences of community. I was proud of my family and what we represented in our small, southern-Ontario town.

And then, suddenly, I wasn’t. I wasn’t proud of my culture. I wasn’t proud of who I was and where my ancestors were from. I didn’t want to be associated with Angola or known as African. For a long time, I disconnected myself from my African bloodline. To this day, I am unsure why.

There was shame; maybe I thought you were not good enough. There was ignorance; your standards of beauty didn’t seem to measure up. There was embarrassment; your history hasn’t been victorious. You were the defeated land, the place that had lost every battle. So please understand that a part of me also felt lost and defeated.

I wanted to escape our connection, relinquish our relationship, cut all ties. Almost instantly, I removed you from my life. I told myself I wasn’t African. I told others I wasn’t African. I omitted certain details from answers to questions about my family. The process of removal was not elaborate or complex—I simply decided one day that I no longer wanted to be connected. I pushed you into a dark closet, locked the door and threw away the key.

It took a lot of growing, heartache and inward reflection to accept that my blood is my blood and nothing can change that. I started with forgiveness. To change the lens through which I saw you, I needed to forgive the person who represented you: I needed to forgive my father for his growing absence in my life. With time, Africa, you no longer represented an estranged relationship. You were part of me that I had neglected for years.

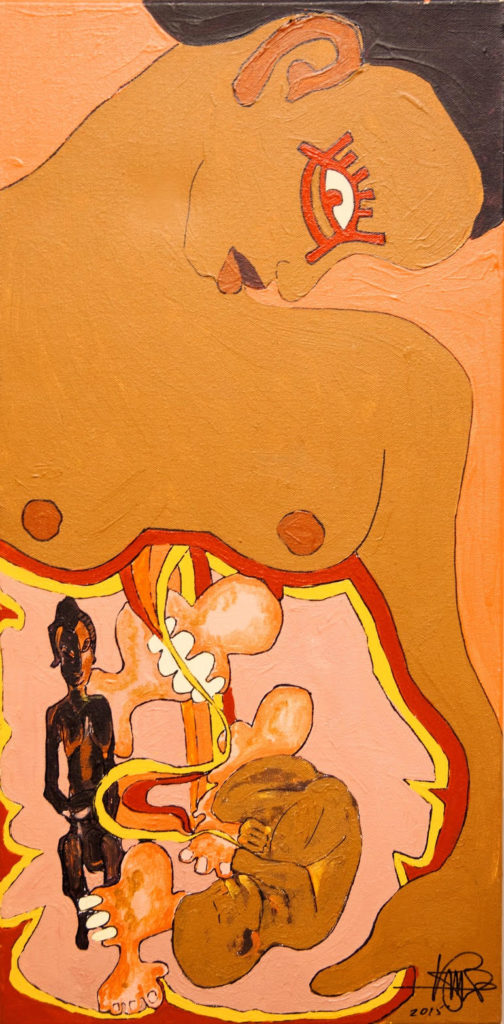

Today, I see your beauty. The face of my grandmother. The faces of the Mandume women whose tribal blood runs through my veins. The faces of the Mwila women whose dreadlocked hair resembles mine. When I catch my own reflection, I see your details in my face. My eyes, nose and lips resemble that of your beautiful warrior people. I share their blood. My daughters share their blood.

Africa, I now long for the opportunity to meet you. To step onto the lands my father called home. To smell your air. To touch your roots. To feel your sun. I admire you. In a world of constant flux, you continue to prove your resilience. I stand still in your waves of strength. At last, I stand still in your undertow of tenacity. And I no longer run.

You make up everything that is great within me. My blood is thick with your culture and rhythm. My blood pulses with your wild tenderness; your mysterious softness. An unstoppable current of unchangeable identity. I am grateful to have finally found peace in your arms.

With love,

Ciana Paulino