Greetings from the Adirondack chair on the sunny side of my porch, on the outskirts of a small town, on the coastal edge of that province waaaay over on the eastern edge of the country….

There are no other buildings in my view right now, just the afternoon light on the harbour, yellow leaves falling from birches, a few bees foraging the last of the black-eyed susans. By evening, it will be so dark I’ll need a flashlight to visit my neighbours (you don’t notice streetlamps until there are none). By the end of October, seasonal businesses in town will have closed and by mid November, streets will be deserted at dusk. Any stray tourist would say this place is dead.

But rural and quiet—even officially closed—should not be confused with lifeless. Lack of high-profile events or line-ups outside venues does not mean lack of workshops, performances, readings, or exhibits. It doesn’t mean things aren’t happening. You just need to know where to look.

There’s a band playing Thursday night at the microbrewery and a film screening at the parish hall. A quilting class started up in the building next to the feed store. That new shop on the main road will special order canvases in any size you like. The bookstore closes at five—but the readings start at seven. Just wait, ask, search. And if you don’t find the events, supplies, mentors, or audience you need, make it happen anyway. Outside big cities, you have to be creative about being creative.

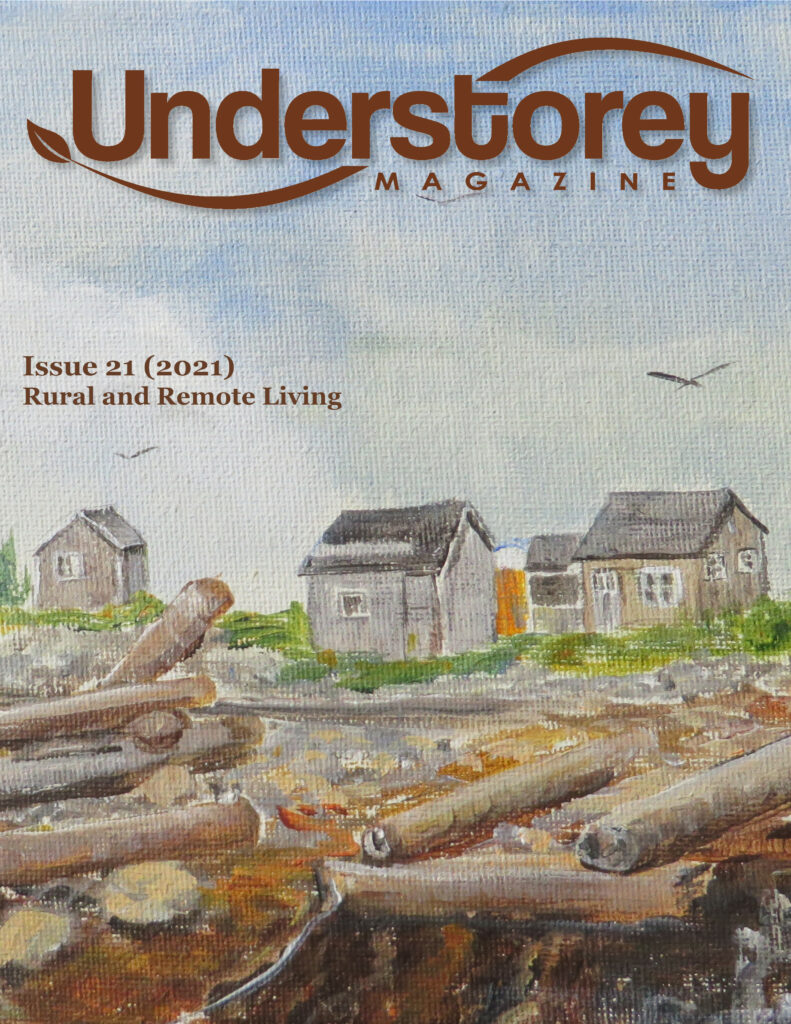

Cover art: Storm Tossed by Marg Millard

In the submissions for this issue, all from “creatives” who live outside large urban centres, I read about the beauty of rural and remote lands and how the natural world provides constant inspiration, through awe as well as an urgent compulsion to protect. I read about the less frantic pace of rural life and how this often provides the means and will to create. I also heard about deep connections among rural people, the interdependence of communities and their inhabitants, whether separated by a field, an inlet, a long snowy road, or intermittent internet.

There was ambivalence in the stories and images submitted to this issue, too. A love-hate relationship with rural living. Out-of-the-way does not mean unspoiled or uncomplicated. Rural and remote areas can be dumping grounds for urban waste, testing grounds for half-baked business ventures, forgotten grounds of abandoned homes, clear cuts, mine pits. And sometimes, unfortunately, they support an insular thinking that can feel judgemental if not suffocating.

But I also found downright frustration in the voices of writers and images of artists, either hidden between the lines or stated explicitly. Not frustration with insular thinking in rural communities but rather with insular thinking about rural communities: The sense from urban dwellers that rural is where you go when something bad (or nothing at all) happens, or rural is where you’re from before something good (or anything at all) happens. The feeling from city creatives that all rural people—and therefore all rural stories—are the same. The failure to recognize the unique challenges of being a writer or artist far from urban centres.

The shift to Everything Online has been a mixed blessing. It has blurred the urban-rural divide, allowing a writer in Canning, Nova Scotia, for example, to attend TIFF and a street artist in Twillingate, Newfoundland, to share work at a festival in Milan. It has also, for better or worse, offered those in urban centres a glimpse of rural constraints and forced us all to be even more creative about being creative.

Of course, there is no substitute for in-person experience. As venues open up, let’s hope that events, audiences, and opportunities move in both directions, from downtown to farm gate, from inner-city to outport, and back again. Let’s hope that everyone, everywhere has the opportunity to appreciate the extraordinary diversity and talent of “rural creatives”—perhaps beginning here, with contributions to this issue of Understorey Magazine.

About our cover artist and print edition

Our cover artist for this issue is Marg Millard. Marg has been an enthusiastic supporter of Understorey for many years, “liking” and sharing almost every single social media post we publish. Her painting Storm Tossed shows the area around Coffin Island, Liverpool Bay, Nova Scotia, after a major storm.

Understorey Magazine has been published in rural Nova Scotia—near E’se’katik or Lunenburg—since 2013 (in partnership with Mount Saint Vincent University in Kjipuktuk/Halifax). We are primarily a digital magazine but will be creating a limited-run print edition of the Rural and Remote Living issue. Also produced and printed in rural Nova Scotia, this edition will be made available to all contributors and their communities, partly in recognition of unreliable internet service in many rural and remote areas. For inquires about the print edition, please email [email protected]

About Katherine Barrett

About Katherine Barrett About Natalie Meisner

About Natalie Meisner About Heidi Jirotka

About Heidi Jirotka

We Still Return for the Cod by Kat Frick Miller

We Still Return for the Cod by Kat Frick Miller