Winter. Discontent. There’s a reason Shakespeare bound those words for eternity.

When I was a kid, winter meant a puffy new coat, tunnels through giant snowbanks, and sweeping, ephemeral snow angels. Though I loved that first day of spring—running shoes on pavement!—I loved the whole winter, too. It was simply part of the year, part of life.

Now, as a trudging adult, winter means work. I blindly hope it won’t happen, that it will somehow pass me by. When winter arrives, as it always does, I feel injustice: What? Snow, again? I shovel the driveway, find mitts, wipe salt from the kitchen floor, find mitts, dry boots on the radiator, and find those very same mitts once again. The possibilities of winter are stifled beneath the weight of getting things done.

Of course, there are parallels to the creative process. Watch a kid who loves to paint or write. The first brush stroke or sentence, like that first plunge in the snow, begins an adventure, opens a portal to everywhere and nowhere at all. It’s thrilling. It’s magical. And then, well, it’s time for dinner….

But to be serious artists we must indeed be serious. Product matters. Success matters. We must buckle down, finish our work, package it neatly, and ship it out to the world. And then we wait as our creative offspring is surveyed, judged, scrutinized, and more than likely shipped right back home again. Turned down. Rejected. Like the fifth winter storm in February, rejection is unfair, infuriating—and inevitable.

The literary world is infamous for copious and cryptic rejection. Top literary magazines reject 99.9 per cent of submissions and most with a form letter or cold silence. The writer is left with nothing but their boomerang prose and a creeping sense of failure. No doubt visual artists vying for their first show experience the same.

I’ve dealt with rejection from both sides. As a writer, I’ve amassed my share of eternal question marks and Dear Submitter letters. As an editor, I can attest that sending rejections is the very worst part of running a magazine. Understorey is small and dedicated to nourishing creativity, so we try to respond to each submission with a personal note, either an acceptance or a reason for rejection.

Still, every writer and editor knows that rejection is part of the deal. Like winter, it will come. To ease the blow, we offer Understorey‘s alliterative emergency kit: four small Rs to better prepare for the the Big R.

1. Revel. Go on, take a moment to wallow. Feed your rejection letter through the shredder. Toss your writing guides in the compost. Furiously clean the house because that, at least, is productive. You might even co-wallow at places like Literary Rejections on Display, a nine-year-and-counting collection of merciless brush-off. Raise a glass with fellow failures everywhere!

2. Reframe. In the sober moments following your rejection-fest, you might consider the wise words of researchers who study failure for a living. Carol Dweck, for instance, suggests we reframe failure as “not yet,” as a necessary, neuron-building rung on the wobbly ladder to success. In Outliers, Malcolm Gladwell concludes that greatness requires a degree of aptitude and a ton of work—10,000 hours of work to become a virtuoso. So, yes, the early stages will be tough, collect yourself. In the immortal words of Debbie Allen: You want fame. Well, fame costs….

3. Recruit. You need to get to work. But given that two-word rejection letter, where do you start? How can writers improve when writing markets provide little or no evaluation? Some guidebooks are great; retrieve yours from the compost bin now. Writing websites offer valuable insight, too. People are best, of course, but finding available, willing readers to provide honest, constructive critique is tough. I’ve considered starting a match-making service through Understorey where writers can exchange work and feedback. What do you think? Would you use it? (Leave a comment or contact me.)

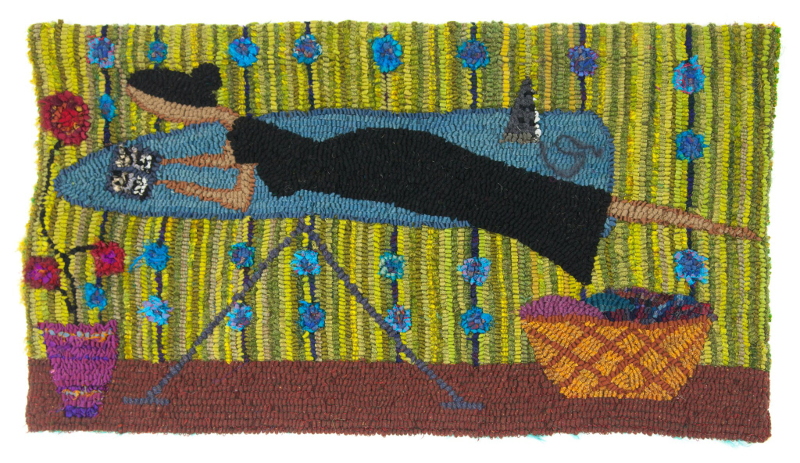

4. Regress. Yes, we need to work hard, get things done—but not all the time. Nearly every instruction on writing (and no doubt on other creative pursuits) suggests daily doodling, a time to create without critique. Natalie Goldberg popularized the idea of free writing, during which “the correctness and quality of what you write do not matter; the act of writing does.” There is no goal, just childlike freedom play. Goldberg and many others promise this practice will restore your spirit and improve writing. So put down the snow shovels, writers and artists, find your puffiest coat and the fluffiest snow drift. Fling yourself backward. Make angels.