It happens as Al is walking home, her hands thrust deep into the pockets of her overcoat. Usually she is on her guard at such times, wary and aware, but tonight she is high on a night out with the old crowd—Sam, Jess, Billie, Little Jo, who’s just Jo now that Big Jo is gone. The old bars may be closed, but when they get together it’s easy to forget that the past is past and the present a different animal. Her heart is full, her step is light, and she fails to notice the two men who slip out of the shadows to follow her. It isn’t until they are nearly on top of her that she hears them coming, slipping and skidding on the last of the February ice.

When she was young and full of fire, she would have been ready for them. But she is too old and they are too fast, their fists in her jaw before she can get hers up. Under the eerie amber glow of the streetlights their faces are alien and fierce. She can only pick out the odd detail, here and there: a beard, a torn jacket, a belly tight and round as a drum.

They beat her until they get tired of beating her, and then they leave her lying on the sidewalk, staring up into the night sky. A few tattered wisps of cloud blow across the face of the moon like so much trash.

Al does not call the police. She is old enough to remember the days of bar raids and paddy wagons, when anyone not wearing at least three pieces of women’s clothing would be arrested or worse. And there was always something worse. Things may have changed, but she doubts they’ve changed enough.

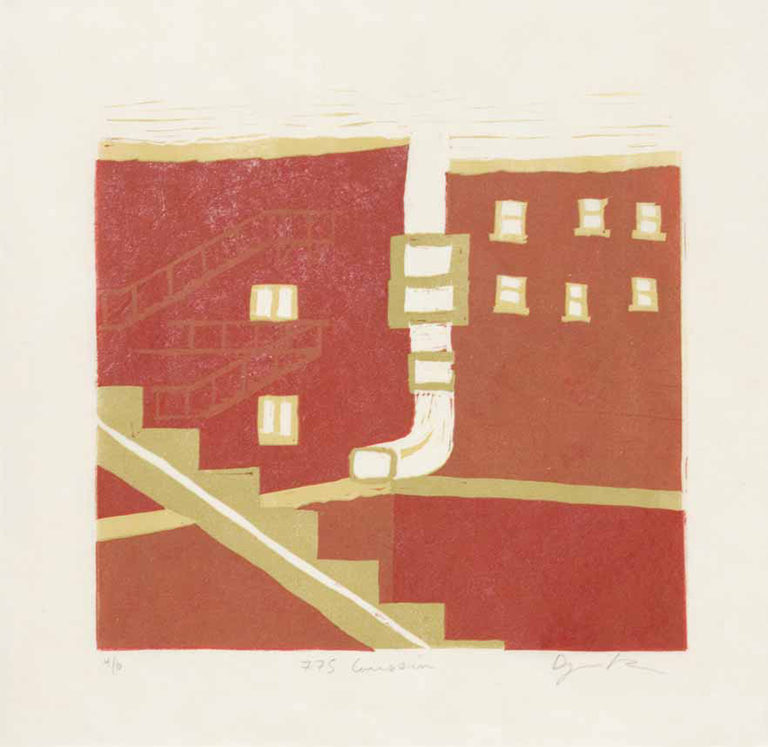

Red and White Series 3 by Shreba Quach

After she drags herself home, stopping every few minutes to rest, she stands in front of her bathroom mirror and surveys the damage. Her left eye is swollen and plum-purple. Her nostrils are crusted with red, although the nosebleed has stopped. Her ribs are sore, but not broken. She’s had ribs snapped before, and she remembers the way they burned when she drew breath.

She’s lucky. It being a festive occasion, she went out wearing a full suit. And a tie can be a noose in the wrong hands.

Aside from her dignity, what has suffered the most is her shirt. Blood has soaked into the collar, crimson blooming on the fine white linen. Al stares at it hopelessly, plucking at its edge. Frances would know how to treat it, what mysterious bubbling liquid to dab onto the fabric to return it to its former glory. Magic, she said once when Al asked her how she did it, smiling that wry little smile of hers. Al hadn’t pressed her. Women need their secrets. Lord knows she has enough of them herself.

The shirt will have to go. Al tears it open, wincing at the bruises already blossoming on her arms. She balls the shirt up in a wad and walks into the kitchen. A takeout carton from last night’s dinner sits on top of the garbage can and the smell of it stops her in her tracks. Her nose twitches.

Vinegar, she thinks. She remembers Frances standing over the kitchen sink with a bottle in her hand, dousing a stain and pressing it with a cloth. For the next few days the tang of vinegar had overpowered all other smells in the apartment: the potpourri in the living room, the discount flowers Al brought home from the supermarket, the dark spot on the bedroom carpet where Frances had once spilled a bottle of perfume.

That spot is what’s left of her now. The spot, and the pictures on the walls, and the potted fern on the windowsill that somehow hasn’t died yet. Even her ashes are gone, sent to a cousin out west. She counted as blood. Al didn’t.

The vinegar is hidden at the back of the fridge, between a jar of beets and an orphaned can of beer. Al brings it to the kitchen sink, upending it onto her collar. She dabs at the stain with a tea towel the way she remembers Frances doing it: firmly, gently. One of her arms is stiff where it was kicked, and moving it sends white-hot darts of pain up into her shoulder. She ignores it and keeps going.

At first nothing seems to happen. Then, after several minutes of blotting, the red seems to be more of a pink. The pink turns to blush, which turns to only the faintest sigh of colour on the white. You’d have to have your nose pressed close to her neck to notice it at all.

Al runs the shirt under a cold tap and drapes it over the back of a chair to dry. Touching the collar, she glances at Frances’s fern, lush and green against the darkness of the kitchen window. The plant looks lonely, she thinks. She’ll have to get another to keep it company. Something strong and beautiful, vibrant and sweet.

Al washes her hands. She brushes her teeth. She goes to bed and imagines the plants she’ll buy, violets and geraniums and philodendrons bursting riotously out of their pots. It will be spring soon. The winter will end.