There’s a video that periodically haunts my Facebook feed under “suggested for you.” It’s of a hippo saving a helpless little impala from being attacked by a crocodile. The impala is stranded on a tiny island and is forced to enter crocodile-infested waters in a desperate attempt to make it back to shore. A crocodile catches sight of it and zips up from behind. Just as its jaws are about to snap down on the poor impala’s torso, a hippo intervenes. There’s a dramatic underwater wrestling match but the impala springs up and safely makes it to shore.

Sometimes I’m served different versions of this video, showing the same cast of characters but with ominous music, multiple camera angles, and an odd montage of stock footage. There’s nothing particularly troubling about the videos (the impala always makes it in the end) yet I flinch every time I see the videos in my feed. For some reason, the algorithms served up this story to me—knew that at some point I’d watch it when I was online late at night and searching for new ways to save my family.

*

Last February, when most people around me were going about their normal lives, I quietly began preparing my family for a range of worst-case scenarios. I had read articles about the mysterious virus causing pneumonia-like symptoms and although the odds of a global pandemic still seemed slim, I liked the thought of being prepared. I didn’t buy up all the toilet paper in town but after my kids were in bed, I kept busy with over-planning. I scraped together a two-week supply of canned goods, stayed up late blanching carrots and stuffing kale into small freezer bags, and kept tabs on social posts from friends overseas.

I ordered a cheap inflatable kid’s pool on a March night. Rational me was living in March but pandemic me was already five months ahead, in an imagined worst-case scenario where my family was quarantined during an unprecedented heatwave. I imagined the supply chain collapsed and the window air conditioner that cools our tiny apartment broken or not working enough to spare the kids from heat exhaustion. (As it turned out, our city did have a heat wave and there was a shortage of outdoor toys but our window air conditioner held on.)

I’m a journalist and trained to filter facts from fear and sift through mountains of information to find trusted sources. But I am also the mom who broke down in a Sobeys aisle on a Wednesday afternoon, when the grocery store shelves were bare and I was wondering if we would ever find diapers or carrots again.

*

About a month ago, I had a vivid dream. It was dark and I was standing on the deck of a marina near a lake where a few sailboats had docked. People were hanging off every part of the boat, drinking and wearing crop tops and just living their lives. Then out of nowhere, a massive, muddy wave swelled behind them and enveloped the boats. I screamed but when the water receded, I saw that the people had held on and continued as if nothing had happened. More waves crashed down yet they continued to emerge unscathed and the scene kept repeating itself as the waves got closer to me. I stood there desperately trying to figure out if I was the only one sensing the danger and if it was okay to feel this afraid.

*

By April, I knew of friends and colleagues who were sick. It was closing in on us and I scoured the internet for any new info I could find on COVID-19 symptoms, asymptomatic symptoms, how to spot COVID toes in children, the best face masks for kids, survival rates of people with asthma…. As expected, my social media feeds were filled with ads promoting everything from face masks to remote real estate to toilets (perhaps from my attempts to find toilet paper in stock?).

That’s when algorithms began suggesting the impala video and a stream of related videos, all showing various rescues: Animals saving helpless animals (like the hippo and impala), humans saving baby animals, dashcam footage of people performing CPR on a newborn baby. My stomach lurched each time—it was the last thing I wanted to see at a time like this—and I almost always scrolled past. But occasionally, a headline would hook me or I’d hover just long enough for the video to start playing and I’d know the algorithms would continue to find me.

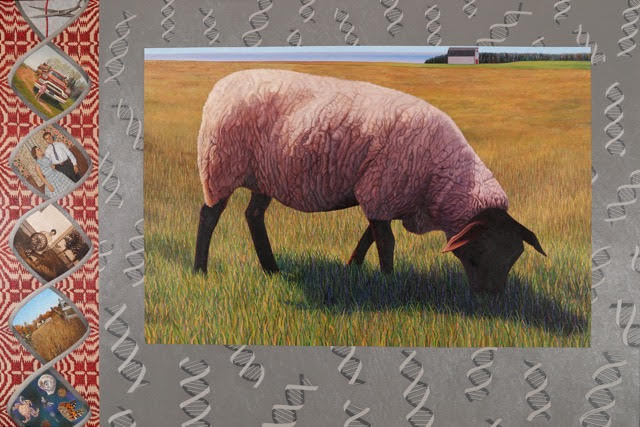

Fabric of Life by Brenda Whiteway

Algorithms are sets of calculations or steps that can solve problems and complete tasks. On websites and social media channels, they can analyze data, often drawn from our online behaviour and actions, to make predictions and play matchmaker. We see and read things that are more interesting or relevant to us (and hopefully stay a while or make a purchase). As we disclose information, read posts, and click on things, we kick up data about ourselves.

But sometimes it can feel like algorithms have a deep understanding of my needs, even before I do. Sometimes I’m no longer sure of when my actions are influencing the algorithms and when the algorithms are influencing me.

I watched a video where a young woman finds a baby shark on a sandy beach and drags it back into safe waters. In another video, a fox pup gets stuck between two fences, separated from its mother. A family rescues the pup and nurses it back to health but the mother fox knows her baby is there and comes back. She rips apart the backyard in a spectacular display of maternal rage—the remains of what looks like an inflatable pool strewn across the yard, arms ripped from dolls—as if to say, Give me back my baby now! Or at least, Don’t forget I’m still here! The human caregivers hatch an elaborate plan to reunite them and fuzzy footage shot at night shows the mother fox picking up her baby by its scruff. They run off together, reunited at last.

*

We were fortunate to be isolating during the pandemic yet I was buckling under the weight of trying to give my kids a “normal” life from inside our bubble. My daughter had ballet classes over Zoom and we played games, listened to records, and danced. We turned down the radio when the news updates came on but there was often too much worry to contain.

Rational me took comfort in the statistics and survival rates for kids but I still held them tightly each night. My partner and I had our babies a little later in life and have health issues. When the kids were fast asleep, I scoured online forums looking for answers to the one question I couldn’t find a statistic or scenario-plan for. But who will take care of the kids if we get sick?

One night, I assembled small packages of family heirlooms and memories for each of them, just in case. I thoughtfully divided jewellery, printed photos, and random things I’d tucked away in drawers, like their first scribbles and the tiny hospital bands we’d snipped from their wrists in the days after they were born. It was therapeutic in a way because I realized that I am not actually afraid to die—I’m afraid to leave my kids.

I tell my children I love them ten times a day but can never find the right words to describe the actual extent of my love. When I try to think of the words, I instead visualize random objects overflowing, like a flower vase left under a running tap in the sink. During a crisis, that overflow of love gets funnelled into over-planning. I perform a sequence of small actions, as if I’m spinning them a safety net made from random tasks they will never know about. I have always worked hard at keeping them alive. I hold their hands as we walk across swimming pool decks, slice their grapes into quarters, keep them away from unleashed dogs. I transfer a few dollars into a RESP each month. Rational me says this isn’t the right time but pandemic me is parenting a decade in the future, just in case.

*

In a latest dream, I am on the edge of a diving board above a public swimming pool and there is a long line of people behind me. Everyone’s telling me to go ahead and jump in with my baby in my arms, to not worry so much. I do jump but when we plunge underwater, I can no longer see him in my arms (or anything else for that matter). I start to panic and hold him as close as I can. I frantically kick my legs to get back up to the surface before he slips from my grip or tries to take a breath. As we burst out of the water, I look into his stunned little face and his wide brown eyes directly in front of mine and I’m certain he’s terrified. Then out of nowhere, he breaks out in the biggest smile—completely unaware of the danger that had just surrounded him.

Stacey, this story is tremendous. I love how you captured the tension parents feel many times, but also how it has been heightened with the pandemic. Thank you for this.