Richie and I were almost finished our morning constitutional, once around the lake, when he sprang it: “Why don’t we have a baby?”

The call of a passing loon muzzled my response as I stooped to pat a French bulldog, a veritable blob of lard on the trail. These pre-work strolls are one way of fighting our middle-age spread. More importantly, they’re a chance for me to see dogs. Richie isn’t a dog person.

Straightening up, I brushed a pine needle off his jacket’s Why sleep with a drip? logo.

“That is so juvenile.” I laughed and sipped my Timmy’s—double-doubles also part of our routine. Richie gripped his cup in his teeth, felt for his keys. A plumbing contractor, he’s always feeling for something. Likes a bit of fresh air before facing the day’s “sore” gas, as he pronounces it.

“I’m serious,” he said.

I listened to a squirrel nattering, gathering acorns for winter though the leaves had only just started to drop. A Shih Tzu charged after the bulldog. Neither breed makes great petting material, as I prefer larger dogs. Given the slim pickings, I might as well have been at work, getting ready to open the shop. Then Richie blindsided me again: “Here’s the deal, Cher. I’ll give you a dog if you give me a baby.”

Like being laid into by a Bullmastiff, I nearly fell out of my flip-flops. Next, it was as though some pricey shop swag had tipped over and smashed: we both went mute as if gauging the damage. Birds and squirrels alike shut up. You could’ve heard a salamander scoot for cover. Richie was serious?

“I mean, hon—you’re not exactly a teenager.” He shrugged helplessly. “Piss or get off the pot, right?”

“A baby? Really? For starters, you have to take classes, learn to breathe and that.”

“You can’t just get that on YouTube?”

“Drive me to work.” I centred my thoughts on the relaxation CDs collecting dust in the shop. Would pairing each six-disc Call of Nature set with a pine-scented candle help move them?

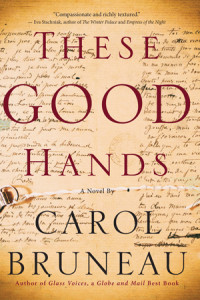

Autumn Flower Brick by Joan Bruneau

Richie didn’t speak again until we got in the truck. “We’ve been together three years. Isn’t a baby the next step? I mean, where else can the relationship go? Think of the fun we’d have making it.”

Fun. My libido was a twinge roughly in the vicinity of the IUD I hoped to have removed someday before I expired—and not in hopes of pregnancy. “No, you piss off. I’m forty years old!” He also knew I’d wanted a puppy since forever, long before he’d entered the scene. “Besides, I know you’re not serious. I see that look you get watching people’s dog videos.”

“Right, I get it. You’re too busy. Scared of being a shitty parent.”

“Sure, okay, whatever.” I took a hasty swig. Lukewarm coffee dribbled down my blouse better suited, perhaps, to a nubile teen. I was happy to have reached the stage where of the three Bs—business, boobs and babies—only the first rated.

“Really, Cheryl. I’m not kidding. You’d be great.”

“You’re being an ass.” I shook his empty cup. “Never wanted a kid before, why now? Feeling your age?” Age was something we skirted, his being four years younger.

We gunned it out of the gravel lot. “Like, all this time building up the plumbing business. Who’ll I leave it to?”

“That’s just BS.”

Yet, dropping me off, he sounded hopeful: “You’ll consider my offer?”

I jumped out of the truck, gazing at the portable sign I rent by the month and have outside the shop. I retrieved a half-eaten burger from underneath it. What every woman doesn’t want: picking up after littering arseholes.

A relief letting myself into the shop. A place where a gal can be at home with her thoughts and feelings without some guy inflicting his: this describes my business plan. Bed to bath décor and self-pampering items for the woman who has everything. And feeling in need of something right now, I bee-lined to the handbags I’d brought in for fall, the best Prada knock-offs available. Faux python, fringed pleather. I selected a rust-coloured one, admired its proportions against mine in the mirror. What I saw was a person in command of her likes and dislikes, of life generally, and not shy about letting anyone know. The purse complemented some other fall merchandise: cinnamon and pumpkin spice candles and marsh heather wreaths decorated with red, orange and gold silk leaves. The comforts and joys of post-Back to School, anticipating Thanksgiving. Shelves of summer stuff hadn’t sold though: beach bling, fairy figurines, tole-painted garden accents, the whole nine yards. But any luck, with kids out of their hair my regulars would have more time to shop.

First things first though, I rustled up the letters to re-jig the signage. What Women Want!!! Endless summer. B.O.G.O.!! Richie deserves credit for coming up with the store name: What Women Want. Not babies, at this stage in life. His oversight stung me. Here’s a man who, at petting zoos, lets goats eat from his pockets but won’t allow a dog in the house. A guy who thinks nothing of unclogging condoms from septic systems yet balks at using one.

I dug for my phone, punched in his number. When he answered, his voice echoed as if trapped in a closet. A trickling sound triggered my need to pee. “You know how I feel about children. How dare you raise it?” I said, and hung up.

Busying myself, I ran the feather duster over some crystal elephants, pigs and rabbits, all sweetly displayed on mirrored shelves, and tidied some hand-painted rocks. I rearranged bath bombs and cupcake soaps so realistic-looking that someone’s toddler had taken a bite out of one. As I orange-stickered the summer clearance stock, a sudden gloom descended: my entire adult life I’d made a point of avoiding exactly what Richie had suggested, starting a family. Though I’d always wanted a puppy, I’d never had space for one. It didn’t seem fair to get a dog then leave it crated all day.

My phone tinkled. Richie. I let his call go to voice mail. I put on a squirrel CD, lit a balsam candle. Composed a pitch: Bring the outdoors to the bedroom, let him take you glamping not camping. The trick, I told my clientele, was letting your man think you were doing it for him: bubble baths by candlelight, juniper and jasmine perfuming the sheets. I dusted the angels by the cash, re-arranged the plaques. My favourite salad is a G&T. Every hour is wine o’clock. Taking a break, I watched a talking dog on YouTube. Maybe I could start a sideline in canine accessories, do for dogs what others had done for cats—but not until the summer merch cleared. I visualised a promotion, Queen For A Day, raffle tickets on patioware with a dollar-store tiara thrown in. Treat yourself!!! If necessary, the beach bling could be stored, cruise season was just six months away. The season of legal abandonment, a mom called it once, juggling twins while she hunted for dragonfly earrings.

Until meeting mothers at the shop, the most exposure I’d had to kids was driving past the daycare. Most people know better than to bring children into the store, thanks to the Break it, you buy it reminders posted everywhere. Fair warning. Still, ladies with babies and toddlers sometimes slip in, quilted diaper bags slung over their shoulders. The awful pastel accessories. Wipes, bottles, diapers, formula. Imagine leaving the house with all that crap. I draw the absolute line at strollers. The stroller stays outside, I’ve said on several occasions. What would I do with a baby? Then there’s the crying.

Fighting my gloom, I imagined Richie’s bribe. Visualized a panoply of breeds. Shepherds, huskies, collies. Sheepdogs, doodles. Beagles, pit bulls, basenjis, rotties, barring schnauzers, cockapoos, spaniels. In a welter of imagined yips, visions of pink and blue suddenly swarmed my brain, a Walmart’s worth of baby stuff. And it hit me squarely, honestly, how wanting things is what makes the world go around.

Things you didn’t even realize you wanted until someone planted the seed.

Especially things that might be harder to get with age.

Something you unexpectedly decide might not be such a bad idea after all.

A baby.

The phone rang. Richie, again. This time I picked up. His voice was a freight train: “You won’t believe this morning’s job. Kid flushed a dinosaur down the john, the mom flushed a diaper. By accident. What was I thinking: a kid?” He was on a break, would see me in a sec.

When he walked in, he was all “Whatcha saying, Cher?” Like the deal had never been proposed and nothing had come between us. His coveralls were stained and he smelled a bit bad. Oddly, he went straight to the purses too, chose my fav.

“You should be home taking a shower.” I waited for him to bring it up. Knock me over with a feather. I wanted him to bring it up.

“Kids running the show at this place. Total animals. The parents, nice people but useless. Epic failures. If I ever mention a baby again, shoot me. No wonder they make you take breathing lessons. Fuck.”

Only then I noticed something moving under the top of Richie’s coveralls. When he tugged down the zipper, a tiny head squirmed free. It was a teacup Chihuahua that just fit in his palm, smaller than a wallet.

“Who knows what got into me, springing that on you? Must’ve been something I was smoking. Us having a kid!? Craziness. Don’t worry, it’s passed.”

Gentle as could be, Richie slipped the pup into my favourite purse. “There you go, babe. Accessorize. ‘Pimp yo’ puppy.’ Like her?”

I held the purse tight. The pup was like a baby kangaroo inside its pouch.

“Looks good on you, Cher.”

It did, and, short of Timmies becoming some magic elixir of youth, I had what I wanted. Sort of.