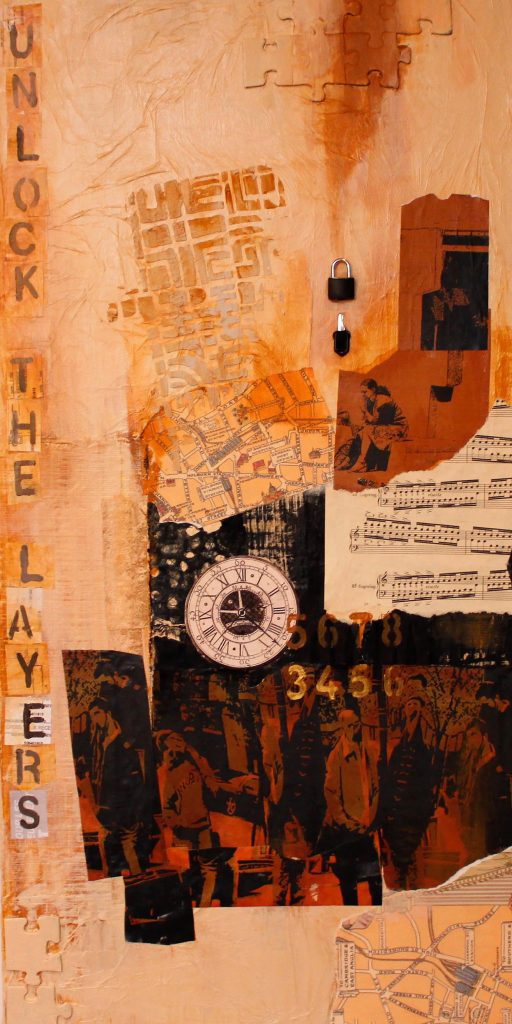

Layers of Illusion by Leah Dockrill

I am eleven and standing in the hallway of my apartment in Block 545 in Singapore. From inside, I hear the horrible sounds of cats being tortured. The only problem is that we don’t own cats. In a panic, I fling the door open and I see my mummy sitting in front of her brand-new musical instrument, a table-sized pump organ. A harmonium that was screeching and bellowing. Mummy looked up at me and laughed; genuine happiness radiated from her. Her eyebrows danced and her lips parted as melodious sounds emerged from her belly. I had never seen mummy look like that. Something was different.

“I have decided that I am going to be the best harmonium player and temple singer in Singapore!” she said.

“But Mummy,” I screamed, “you don’t know any music! You cannot sing. Where did you even get that thing?”

She winked at me. “Meeta, my friend from temple, bought a new harmonium. I grabbed the chance to buy her old one. She even came in her car and dropped it off this morning.”

Then, Mum put her right hand up to silence me. She raised her chin in defiance. “Cannot? Why not? Just watch me. Everything is possible, beti, if you believe it in your heart. Whenever I go to the temple, I watch the priests play beautiful music on the harmonium. I feel happy from inside. It was fated when Meeta said she was getting rid of her old harmonium. The universe is showing me the way. Now, go and eat your cheese bread I made for you.”

My mom was thirty years old at that time. She had been a child bride at sixteen, shipped from Delhi to Singapore, and had lived in a prison of tradition and patriarchal rules. Always silenced. How on earth could she learn music when she was not allowed to go out, talk on the phone, have friends, work, drive, or go anywhere without my father? There was no chance of even getting a music teacher.

As a young girl, I was worried about my mom’s rebellion. I decided that I would keep a close eye on her. Secretly, I spied on her. I was puzzled by the nonsensical diagrams that she scratched in her palm-sized notebook. With intense scrutiny, her nose scrunched, she pounded each key on the harmonium, listened intently and repeated the sound. Then, she drew more secret diagrams with arrows. This went on for hours. She tried to copy English songs from the radio that blasted in the background and the harmonium bleated her Frankentunes.

She practised her music every day when my father went out. She cleaned. She cooked. She prayed. She played on her harmonium. My brother and sister learned to tune her out. We ignored her command to join her when she practised. We shook our heads and burst out laughing; then we ran for our dear lives.

There was more and more laughter in the house from everyone it seemed, thanks to mummy. Absorbed in her self-taught music lessons, she laughed and it filled the house with calm and peace. Papa was a strict man and he expected all of us to follow his rules, especially mummy. I recoiled when Papa’s angry voice boomed through the house if the TV was loud or mummy disagreed with him. Now, this innocent laughter from mum overshadowed the air of dread and smoothed my fears, at least when Papa wasn’t home.

But one day, Papa came home early while Mum was practising. The scowl on his face worried me. I knew that mom’s rebellion would fetch a price. He thundered in the door and bellowed, “You are wasting your time. You will never be a singer or play that thing. Now go and make my dinner.”

Mom laughed sweetly, so as not to provoke him, and said, “Why not?”

I followed her into the kitchen. She hummed her tunes and swayed her head. She winked at me and I swear she put extra chilies in Papa’s portion of chicken curry. Then, she hugged me and giggled like a teenager. Her quiet laughter reverberated round the apartment and cocooned me. The tension slowly dissolved. I even heard Papa chuckle.

And so this madness from my mummy went on. Music. Laughter. Singing. Two months later, I came home from school and heard a familiar tune I could not place. My mom looked up at me with her smile and said, “I am playing ‘Like Virginia.’” She played the tune again. Suddenly, it hit me. “You mean, ‘Like a Virgin’? By Madonna?” My mom threw her head back and the sounds of pure joy gurgled from her belly. The red dot on her forehead between her dancing brown eyes bobbed up and down. “Yes! The one with the pointy….” Her hands waved around her breasts. “Moooommmm,” I screamed and danced like Madonna while she played her bizarre Indian version of “Like a Virgin.”

Eventually, mummy joined the women’s singing group at the temple on Wednesday afternoons. The temple was the only place she was allowed to go alone, and my father dropped her off and picked her up. I heard such raucous laughter and music erupting from these gatherings on the rare occasions that mummy succeeded in dragging me with her. The women sat in assorted groups, cross-legged on the carpeted floor, enthusiastically discussing new tunes to play. Some would beat the tablas. Others grabbed finger cymbals. Together, each group created harmonious new hymns. They laughed without worry or censure, safe in their collective space. They clucked like hens when they disliked a new tune. They guffawed in approval when they perfected a tune. Even I picked up the finger cymbals and joined in with mummy’s group.

Today, mummy has sung in temples in Indonesia, India, Australia, and Calgary. No one can stop that five-foot-tall woman. With her megawatt smile and infectious laughter, she brazenly invites herself to any temple podium that she can, anywhere in the world. She has even played for the Prime Minister of Singapore at the Singapore National Theatre!

Growing up in that house, I learned the meaning of passion. Within the confines of her tradition, mummy created music and laughter—she created harmony. She permeated the walls with mirth. And as a young girl, I too started to believe in possibilities. I began to learn how to manoeuvre those restricted wings, quietly and covertly. Now I toss my head back and laugh from the depths of my soul whenever I think of my mummy. Because that’s how she now laughs. Eyes twinkling. Cheeks dancing. Unrestrained music that rises to the sky.

Listen to Kelly Kaur read “The Music of Laughter.”