I am awakened by the sound of my phone. I glance at the time before I answer: 4:00 a.m.

“Hi Mom. What’s up?” I try to sound awake.

“Cecile,” she gasped, “you have to help me … call my doctors. Tell them I need to go back to work. If you call them, they will listen to you, but they won’t listen to me….” She continued talking. It didn’t matter if it was day or night. It didn’t matter if I answered or not.

*

On July 28, 2008, my mom was on a field trip with a group of students and child/youth workers. What should have been a fun, exciting day turned tragic. She stepped off the bus and into the path of a vehicle. She sustained many injuries — broken bones and lacerations. But it was the injury we could not see, the traumatic brain injury, that has brought the most challenges to her and our family.

Until my mom’s injury, I had no idea what the term “traumatic brain injury” even meant. Yet in Canada, fifty thousand people a year sustain brain injuries and over a million live daily with these struggles. Depending on the area of the brain affected, repercussions vary. For my mom, the injury affected her frontal lobe. Doctors said she’d never return to work and would require twenty-four-hour supervision.

My mom is a strong, independent woman. Trying to convince her of these changes while living fifteen hundred kilometers apart has been far from easy. My father was her main caregiver after the accident, but he did not weather the storm very well. Phone calls were difficult: “I don’t know what to do, dear. I just don’t know what else to do.” I could hear the weariness in his voice.

When my mother’s emotions ran high, she ran too. One night about three months after the accident, she slipped out of the house and four hours later, at three in the morning, someone brought her home. They had found her sleeping on a bench down by the bay. The more upset and angry she would get, the more her other deficits, such as facial recognition, would emerge. In a fit of rage she once tried to kick my father out of the house because she thought he was an impostor.

Although some days were without major incident, none were easy. The doctors told my father that almost ninety percent of marriages fail after traumatic brain injury presents in their lives. He was determined to be in the ten percent and I admire him for that.

But as calls from home became more scattered and hard to follow, I began to feel uneasy. I made the decision to fly home for a few days, to try to sort things out, and to get my mom back on track with her medical appointments. It was January 2009, five months after the accident. I expected to be confronted with challenges, but what I walked into was utter chaos: dishes piled everywhere, unopened mail strewn about the living room, and my mom clearly overwhelmed, devastated.

In need of insight into the emotional and behavioural changes in my mother — and ways to help both parents — I requested and was granted access to her medical assessments. I found them fascinating. I learned the functions of the brain, that the left frontal lobe deals with language and positive emotions while the right controls non-verbal aspects of communication and negative emotions. In my mom’s case, the entire right frontal lobe was damaged as well as part of the left. I poured over her medical results looking for a new picture and a new way to navigate her recovery.

Getting my mom to her medical appointments was very challenging. “I hate them!” she would scream. “They make me so angry! There are so many doctors, so many appointments. They make me feel stupid!”

My father and I agreed that she was especially distraught following her rehab and therapy appointments. I watched her closely when she returned from the next two sessions. She was right. Clearly, they were not bringing the results we needed; each appointment only seemed to increase her anxiety and frustration.

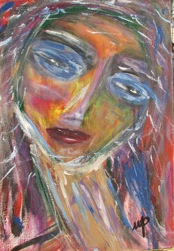

One afternoon, a few days before I was scheduled to fly home, my eyes landed on a large canvas in the hallway. I hadn’t really noticed it before but now something captured my interest. It was a sketch of a sad girl with writing at the bottom. I recognized my mom’s handwriting. She never “did” art before the accident. I was intrigued and the words stirred a deep emotion. I had an idea.

“Mom, did you do this?” I asked.

“Mom, did you do this?” I asked.

“Yes! That’s how I feel! I give up!” she screamed. There seemed to be a lot of screaming. “I have more but you won’t like them,” she added with the disdain of an angry teenage girl. “Your father says they are too scary to put up on our wall.”

“Show me, Mom,” I said.

She stomped to the bedroom and started pulling out canvasses from under the bed and behind the closet doors. I was amazed.

“They make me feel better,” she said in a voice still filled with defiance. “I do them when I get home because I hate those doctors. They don’t listen to me and they don’t understand.”

I made a list — and went off to the art store. I filled my shopping cart with brushes, canvasses, and paints. I practiced what I was going to say a hundred times but in the end, it was simple: “Mom, you need to keep painting.”

Tears flowed. She hugged me as I left to board the plane. “We’re going to get through this aren’t we Cecile?”

“Yep, we are going to get through it, Mom. We are just made this way.”

*

It has been six years since my mother’s accident. In that time, she has attended painting seminars that have helped her gain technique and confidence in her art. The negative and dark feelings in her work are not as prominent as they once were. Although she still turns to her painting as a therapeutic process, it is almost as though, over time, the canvas has absorbed the anguish. At the Brain Injury of Canada conference in Halifax this year, my mom’s art was displayed along with work by thirty-one other brain injury survivors.

Art by Wendy Proctor.