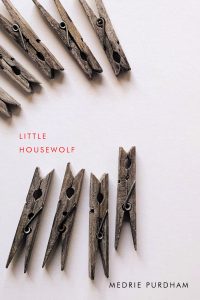

The summary and review excerpts on the front flap and back cover of Medrie Purdham’s Little Housewolf (Véhicule Press/Signal Poetry, 2021) celebrate the considerable skill with which the poet brings tiny, fragile objects into focus—often temporarily into life.

The summary and review excerpts on the front flap and back cover of Medrie Purdham’s Little Housewolf (Véhicule Press/Signal Poetry, 2021) celebrate the considerable skill with which the poet brings tiny, fragile objects into focus—often temporarily into life.

All this laudatory metadata is perfectly true, yet at odds with what I found most intriguing in Purdham’s collection: its teeming menagerie of birds. Whether as specimens or metaphors, lead actors or silhouettes, they are everywhere—roosting and nesting in more poems than not.

The book opens with “Hinge,” a meditation on a creaky old gate that I suspect of being narrated by three birds in a trench coat, pretending to be human: “And every day we came home / […]. Each to his identical little plot / piled high with long mouldy hay and lost plumage.”

From there, the game is afoot: where else are birds hiding in this book that so carefully minds things that are lost in pockets, rolled into corners, almost out of view?

If I could hold Little Housewolf to my ear like a seashell, who would be chirping in the background? In “Carapace,” for instance, the reader is invited to consider crab shells, yet a grandmother’s long-wounded foot has the unfeathered flesh of a newly hatched chick: “tended and collapsed / simmered red”—an image both delicate and unnerving, cooked and raw.

Little Housewolf’s birds are not always doing covert ops, of course. “The Thimble’s Bucket List” brims with birds in useful motion. The thimble in question fantasizes (yes, this thimble thinks thimble thoughts) about being “stolen by a magpie,” brought to a nest, or sacrificing itself to a greater cause “like a stone in the beak.”

The triptych “Ludwig Koch’s Library” turns from the late broadcaster’s professional legacy to his childhood practice of recording bird calls on wax cylinders. Delightfully, Purdham can’t resist mucking about; she puts “wax and feathers” precariously close together, delivering a sticky domestic nightmare to anyone who has ever kept both birds and a record collection.

And then there is the little housebird of Little Housewolf: the dramatic cockatiel of “Kitchen, Vicarious” who “faked an illness” in “her suit, smart grey.” Against Little Housewolf’s backdrop of her figurative and feral cousins, she is a cabaret star fronting a chorus, a smartly dressed TV anchorbird, or prime minister of the parliament of fowls.

I cannot introduce every bird in Purdham’s debut collection, nor should I; Little Housewolf does this more beautifully than I could hope to. Yet I dare readers to find them all—to wrest their attention from Purdham’s exquisite collisions of objects, textural cues, and abiogenesis long enough to notice her quetzals, pelicans, pigeons, flamingos, kites, doves, and sparrows. If they find you first, don’t worry—it’s supposed to be good luck.