Alisha Kaplan and Tobi Aaron Kahn’s Qorbanot: Offerings (SUNY Press, 2021) is a gift of candour, scholarship, history, and future. Its substantial, glossy pages relax open (on a table, a lap, into the reader’s palms) to insist that we take time to witness its shimmering dialogue between poet and painter. Qorbanot is a particularly complex gift (yes, of course—an offering) that urges us to accept both warmth and pain. I’ve never read a book of poems quite like it.

Alisha Kaplan and Tobi Aaron Kahn’s Qorbanot: Offerings (SUNY Press, 2021) is a gift of candour, scholarship, history, and future. Its substantial, glossy pages relax open (on a table, a lap, into the reader’s palms) to insist that we take time to witness its shimmering dialogue between poet and painter. Qorbanot is a particularly complex gift (yes, of course—an offering) that urges us to accept both warmth and pain. I’ve never read a book of poems quite like it.

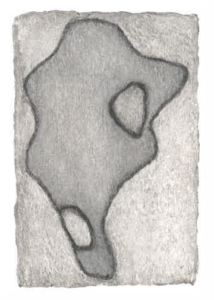

At first glance, Kahn’s paintings appear abstract, with controlled colour palettes, undulating shapes, and strong outlines—jarringly close (like microscope slides) or assertively distant (like topography). But to neglect the context of Kahn’s paintings—their titles (named “studies,” all), their intimate relationship with Kaplan’s polyphonic poems—is to close oneself off from the experience of Qorbanot. In dialogue with Kaplan, Kahn’s art becomes figurative and emotive, yet just out of reach, “like [prophets] looking into a dim glass” to glimpse God (110).

Kaplan and Kahn each descend from families that survived the Holocaust. That shared inheritance is a canvas for their multi-genre exploration of Jewish identity across millennia, of building one’s own narratives as a young person raised in safety and abundance, of grappling with the profundity of love stolen back from the jaws of hate. “How can I deserve this love?” (67) asks the poem “Offering to My Mother.” Just below is a small image of “Study for TZZAK”—two soft grey shapes at a distance from each other, yet enclosed within an uneven boundary (image on right; published with permission).

The poem I cherish most is “Offering of Seven Heavens” (96–98), followed by the painting “Study for LEHU” (99): wobbly white bodies (maybe orbits) in a dark blue-grey expanse, banked by more cottony, sandy white—seven layers in all. Kaplan’s poem is similarly evocative. Each of its seven sections looks boldly upward: “I was taught in school to stare at the stars / is idol worship.” But we “roll up the apocryphal curtain” anyhow. The heavens are an “upturned bowl” (a familiar domestic scene; a child’s makeshift toy) but “the stars are not fastened. / They don’t wait for our sacrifice.”

Kaplan’s closing words arrive in the form of a short essay. “Avodah” (105–110) explores an idiosyncratic rite of passage undertaken at age 30: digging her own grave, wrapping herself in a sheet, sleeping in the earth for part of the night. She learns that “a little violence is necessary” (105) to split open the earth and make a quiet, dark place within it. In facing her future and her mortality, she uncovers the soil’s history, “new layers […] brown to dark amber to brick” (105), echoing Kahn’s visual artistry. His final painting is “Study for STARHA,” a flower-like burst of blue and white on green: bright, defiant colour and energy after an essay that sits with darkness.

As with Kaplan’s earlier reflection on stargazing and idolatry, I’ve thought about her self-made grave and the emotional and intellectual courage of her poetic voice every day since I finished reading Qorbanot. I’ve done my best to accept Kaplan and Kahn’s offerings, and already know into whose palms I will place my copy next.