The moment I knew it was time to give up sheep farming is etched into my memory. It was late February and lambing season. Checking the barn, I saw a ewe straining. She was trying to birth her lamb, but the lamb’s knees had gotten jammed behind her pelvic bones so that its head was out and swollen. I caught the ewe, carefully reached in, released the lamb’s legs, and pulled it out. I placed the lamb at the mother’s nose, and she started to clean it off while I pulled out the twin.

The second lamb got to its feet immediately, and so did the mother, turning her attention away from the limp first-born, whose head was so swollen that it couldn’t get its balance to stand. The mother’s attention might get it to its feet, but I could also take it inside the house to keep it warm, feed it, and give it time to get the swelling down. Experience said that if I did that, I’d have a bottle-lamb on my hands. I knew I could not handle that task again.

Earlier that year, in January, the same thing had happened. Inside the house, the lamb took all day to get to its feet, and I fed it with a bottle until it did. When it went back to the barn, we made four trips a day to feed it. Back in January, my eighty-year-old husband did half of those trips.

Now, with snow drifted to my waist, filling back in any path I made, he was not able to get to the barn at all. With my off-farm job and doing all the barn work and dealing with the mountain of snow, I could not handle four trips a day to feed one lamb. I walked away, leaving the lamb where it was.

When I went back a couple hours later, driven to check on it, the lamb was on its feet. The mother had done what was needed. But I had not intervened. It was time to quit farming if I could not do what needed to be done.

Six months later, we sold the farm: three hundred acres, two old barns, and a two-storey century home. We left the care of the land in the competent hands of dairy farmers. We suspected that they would take out the fence rows, thereby also taking out habitat for birds, squirrels, mice, and rabbits and removing trees that captured carbon, but they would work the land with sustainable agricultural practices. We bought a bungalow with a finished basement and a decent-sized lot on the shore of Georgian Bay.

When we took possession of the bungalow, the first thing I did was transplant roots, bulbs, and corms from our farm garden into the new garden. The comfrey and orange lilies I had inherited from the family that had settled and maintained the farm before us. Irises came from the home my husband grew up in and from my parents’ garden. The allium and other lilies I had planted. In each case, I took just part of the root, a few of the bulbs, ensuring the plants would still be there for whoever lived in the farmhouse. And for the wild things that ate from them.

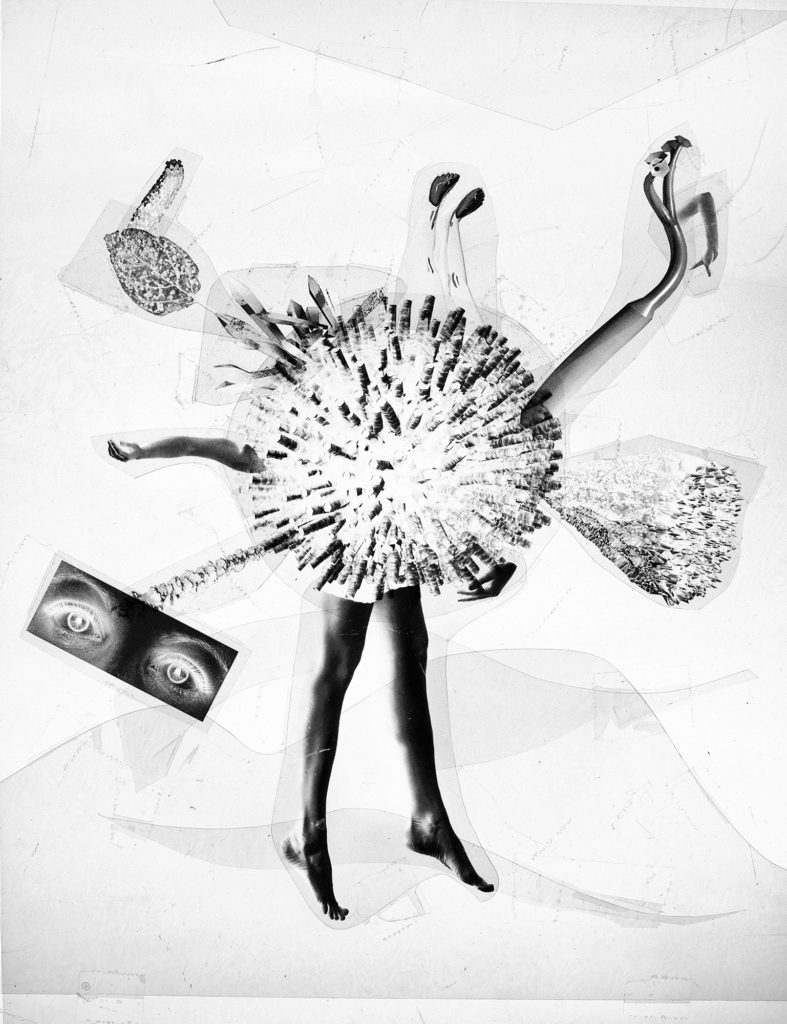

Years Passing / Years Beginning by Brenda Whiteway

In our new house, I planted Jerusalem artichoke and the comfrey, loved by pollinators and hummingbirds, out near the road, a place where they could spread without crowding other plants. With the first lilies I put in the ground, also out by the road, I realized that the soil of our new location was clay; I mixed in generous amounts of compost. When I moved to the place I had chosen for the irises, closer to the house, my trowel bounced when I tried to dig. I cleared the mulch and uncovered landscape fabric.

I stopped. I investigated the rest of the yard. I found that under the gravel on the paths was black fabric. Under the mulch around the trees was fabric. Between the hydrangeas, around the ninebark and Russian sage, everywhere, the ground was covered with fabric. Wild asters and colts foot had found enough soil in the mulch to grow above the fabric, but no roots reached through.

I went back to plant the irises by cutting through the fabric. I found dead, grey clay. No worms or insects or roots of any kind. I ripped the hole bigger and put in a substantial amount of composted manure and planted the irises. I worried they wouldn’t survive.

The loam on our farm had been fertile. With plenty of manure to spread and a rotation that included alfalfa and trefoil, the ground was productive. Also, with forty acres of bush and thick fence rows, our carbon footprint was pretty well zero. What we put in the air our trees absorbed. But what about now on my little parcel of land? I wondered what mitigation strategies I could take up in this location.

About this time, I came across an article in a farm magazine about capturing carbon in soil. I realized that although I had much less land, I could intensify my practice and capture carbon in the ground. If I removed the fabric barrier that kept the clay dead, I could regenerate the soil, encouraging plants to flourish. I could capture carbon in living plants and soil as well as the trees on our lot.

That fall, I raked leaves off the lawn and into the garden. I dug them into the ground. Come spring, I carefully cut the fabric and lifted it without uprooting the plants. I dug in the mulch as well as some of the wildflowers that grew in it and were taking over. I planted snow peas around an ash tree. The next year, I decided, the peas would go near the irises. The year after around the lilac tree. They would put nitrogen in the soil while growing, feed us when the pods matured, and get dug into the ground when they were done.

I started a composter. I carefully avoided putting meat into it, as there is a bear and a fisher living near enough, and a fox who visits regularly. The first batch of compost made a tea to be used to water the vegetables. The next batch got dug into the hard ground where I planted the day lilies and old-fashioned roses.

The previous owner left me heavy cement pots. These I filled with herbs, coriander and basil, parsley and oregano. I picked up more pots at the thrift store to plant tomatoes and peppers that I grew from seed under LED lights in the basement. I planted borage in pots and in the empty space behind the shasta daisies, flowers for the bees, and leaves for our salads. I created a small terraced garden for beets and lettuce and zucchini. I don’t grow as many vegetables as I did in the farm garden, but for two of us there are salad greens and some good home-grown veggies. I planted two apple trees. It will be years before they produce, but there will be apples here. Not the wild ones I’ve come to love, but good fruit.

There was a lot to learn. I knew I had to water the potted plants, but I forgot they needed fertilizer more often. That compost tea has come to good use. The climate is different by the bay, with spring coming later. But fall lingers as well. There is a lot of shade, something I did not have on the farm. I’ve marked the sunny spots for next year’s planning.

I’m learning to live with the birds here too. The blue jays and squirrels compete over the sunflower seeds. The squirrels spill the seed for the wild turkeys and a couple mallard ducks who waddle up from the shore. We have no barn swallows but the hummingbirds love the flowers, especially the comfrey as it spreads.

I needed to turn away from farming, to leave the livestock and the buildings I could no longer maintain. I miss the acres of land. But I am still a farmer who watches the weather and notices how the shifting patterns affect what grows. And here, on this bit of shoreline, I do what I can to bring life.