Shannon runs her fingers over her upper lip and chin, her way to tell when two weeks have passed. With the esthetician closed in Queen Charlotte, she wonders how long she’ll last before she will pluck her chin hairs, one at a time. Only a select few friends know what grows below her mask. The same is true for her red tunic-like sweater. Daily meetups with recipe books and the refrigerator haven’t only added to her cooking skills but also an inch to her waistline. She squeezes her legs into her pants, feels the pinch of the jeans’ button.

The phone rings and it’s Roz, one of Shannon’s few in-person contacts. Twelve years her senior, Roz is fearless when it comes to sharing her opinions, most of them well-founded. So, when Roz asks Shannon to come over, Shannon looks forward to tea and conversation, but doesn’t expect to hear: My freezer quit working.

Shannon grabs her license and her raincoat and goes to her car. Empty spruce cones squish below her soles; the squirrels have been busy all winter. When she turns the key in the ignition, she gets the same warning as a few days before. The cooling fluid is almost empty, although she filled it just yesterday. The heater isn’t working, but the radiator might be overheating. She calls the auto repair shop, but they are all backed up, and her car will have to wait for a month. William, one of the owners, says he’ll swing by on his way tomorrow to help Shannon bring it to the parking lot. Best not to have the car stall midway between hers and Roz’s house, so she decides to walk the mile along the highway by the inlet.

Raindrops pelt her nose and cheeks. She lowers her head, pulls the hood’s drawstring closer, her eyes focused a few metres ahead. Spray from oncoming traffic lands on her jeans, grey-brown speckles on dark blue: lingcod colours. No one will offer her a lift, masked or unmasked. Five years ago, she would have run to Roz’s in all kinds of weather. Some aches and pains now take longer to heal.

Rivulets of rain stream from her hood when she knocks on Roz’s door. She fishes for her mask that is now all damp and ineffective. The door is unlocked and she shouts “hello” but no one answers. Shannon walks around the house to the well-insulated basement. She finds Roz bent over; it looks like the freezer might swallow her up. Boxes and totes are piled up by her side. When Roz lifts her torso carefully, strands of hair that are usually tied up in a neat bun look like an assemblage of bull kelp washed up on a basalt shore, the colour of her undereye circles.

Roz fixes her stare at the freezer until Shannon says, “Let me help you,” and lifts out two large turkeys, deer meat, and fish. Shannon has never seen Roz waffling about a decision, becoming immobile. Roz finally says, “My neighbour inspected it, he thought I could try to order a new capacitor and starter relay, but what if that isn’t going to work?” Roz stares down at the freezer.

“I can store most of the meat in my freezer. All you need is to call one more friend.” Shannon carries the half-full totes up to the house, suspecting that Roz’s arthritis may be bothering her today. Then Roz tells Shannon that Annie already agreed to take some of the frozen food.

Shannon says, “But I walked here.”

Roz reaches for her purse, pulls out a set of keys, and hands them to Shannon. “Take my car.”

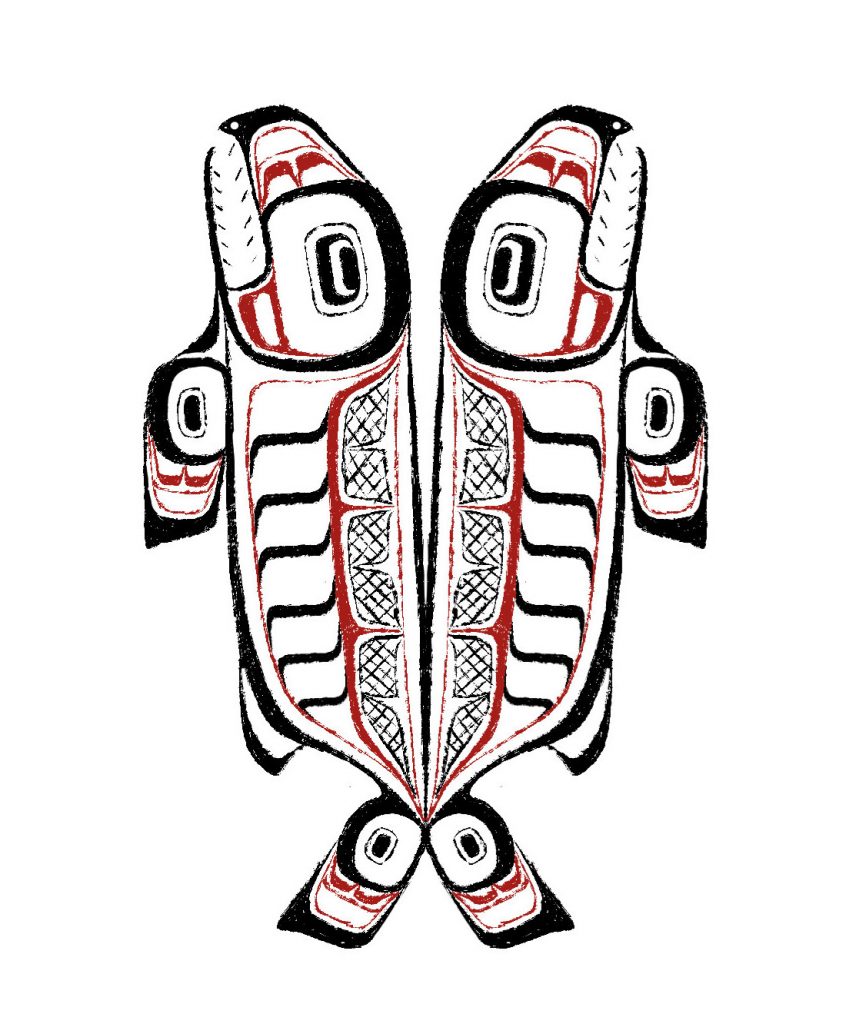

Split Fish by Shoshannah Greene

When Shannon returns from her freezer run to Annie’s, she notices two more totes of fish that will need to be re-homed. Roz has done up her hair again and served lunch from a casserole of Greek pastitsio that Shannon eats with gusto.

“I phoned Kiebert’s, but they don’t have a freezer in store, and shipping one from Prince Rupert will take more than a month.” Roz looks at her lap. “Unless there is a storm.”

“At least we’re used to that,” Shannon says. Groceries in winter may not arrive on Monday, everyone’s shopping day. That is why putting away deer, fish, and fowl is still so important.

Shannon scans Roz’s living room and kitchen. A statue from one of Roz’s African trips sits on a counter, woven hats line the walls with paintings and prints from Southeast Asia. Shannon herself has seen three provinces and travelled once to Mexico before the kids left home. Unlike zipping off a wax strip from her chin, Shannon was slow to remove herself from two relationships, resulting in protracted pain as well as substantial legal fees. Even so, Shannon doesn’t believe that marriage contains a planned obsolescence; Sylvia, her oldest daughter, talks about the institution of marriage in those terms. Take Roz and Ben, Shannon loves to tell her, a couple who met in their twenties are still together in their seventies.

“How is Ben doing?” Shannon asks.

“Okay, he has taken on a lot of his father’s personal care. He’ll stay in Kingston for now.” Roz pours Shannon some more jasmine tea.

“Remember last summer when we were talking about smoking and canning fish?” Shannon says. “We didn’t want to bother with flies so sipping wine on your deck won the day.” Shannon had moved her smoker and canner to Roz’s place in anticipation of a work-bee.

“Good idea,” Roz says.

“Glad you’re in.”

Shannon goes to fetch the totes full of vacuum-sealed fish and cuts them open. She admires the intense crimson of sockeye. Then she carries the two canners up from the basement, one matte-grey like the sky, one a shiny aluminum, and finds canning jars. When the fish has defrosted, she starts a brine. She checks out the smoker on the deck, gives it a quick wipe down. She inhales the faint smell of smoke and salmon—a smell she loves, and one that will ooze from her skin over the next couple of days. At least her fingers won’t be covered in fish scales; that part belongs to last summer’s cleaning and gutting.

Roz winces as she settles into her armchair.

“How is your shoulder?” Shannon asks.

“Some days worse, some days the usual. Thanks for taking the food to Annie’s. I couldn’t have done it.”

“No problem,” Shannon says. “Did they give you a date for the specialist yet?” She immediately regrets her question. So many appointments have been postponed: flights from Sandspit to Vancouver have been cancelled and flights out of Masset are touch and go.

Roz says, “No, everything is on hold,” and she turns her face and pulls up the blanket she got from her last trip off-island. Even a hospital stay would have meant that Roz could connect with her city friends.

Roz suggests a movie, but the download is slow. The twirling symbol reminds Shannon of squirrels chasing their tails. Everyone is zooming and streaming, resulting in low bandwidth. Roz switches to the news and they see a Brazilian woman looking upon a row of dug graves. Roz covers her face briefly then says, “We are so fortunate here.”

Shannon doesn’t respond but goes to put the fish in the smoker; she guesses that Roz is embarrassed over her helplessness. Little by little the old Roz reappears: the Roz who until three years ago caught all the fish herself, who is a skilled cook and makes entertaining look easy. Roz is now on social media, sending pictures to her family, discussing the best lox recipes, best restaurant meals. Roz scrolls through her phone and says, “Martha Brown passed away. She had an aneurysm.”

“This is so hard with only one person allowed in,” Shannon says and thinks about the family-sized palliative care room at the hospital, how no one will go over to sit with the family before the funeral, how numbers for burials will be restricted to the immediate family, and how there won’t be a tea at the community hall with Haida women bringing out plate after plate of salmon salad sandwiches on homemade bread, along with three kinds of chowder and pies.

Still, Roz makes a few calls and announces that this evening there will be a drive-by procession: people can gather by the roadside to show their respect for Martha and their support for the living. Roz places her phone on the counter. Shannon watches as Roz cuts the fish, adds salt and oil, and stuffs them into the jars. “Just like when you’re catching them: a pinch and a wiggle,” Roz says. Shannon laughs and laughs and Roz chimes in.

Listen to Astrid Egger read “A Pinch and a Wiggle.”