Once upon a time, I worked in a research laboratory. I tapped test tubes, swirled flasks and, when strictly necessary, wore goggles and a boxy lab coat. My project, on the genetics of plant disease, offered an intellectual puzzle and plenty of time to tinker with cutting-edge technology. Should I discover it, the answer to that puzzle would intrigue the scientific community, benefit farmers—and afford me a graduate degree.

And yet, this wasn’t enough. I needed something more. So I’d often start an experiment, set a timer and leave the lab. Sometimes for hours.

I’d head to the basement of the student union building, to a scuffed white door with an unassuming sign: Photography Club. There I’d develop and print my weekend shots of birds and trees and graffitied back alleys until I had to rush back to the lab. This was well before Instagram. Photography was messy and magic: an image captured in a blink released into a pool of liquid and slowly nurtured into story. Yes, it felt like pure creation and I was hooked. Throughout my science degree, I developed hundreds of artsy photos. I marvelled at every story that emerged, packed the growing pile of eight-by-tens into black binders and used paper boxes—and printed more.

Then, one day, I stopped. Most of these photos would never be seen. They would not be displayed next to my name and biography. They would not change the world or the way people understood it. They would certainly not help pay my student loan or find a job. Why do it? I’d never asked myself the question and once I did, I found no reason at all.

Why make pictures? Why chisel form from stone? Why assemble words into lines and verse? In one sense all art is storytelling. But why do we tell such stories, especially when we’re busy, broke, stuck, tired or criticized?

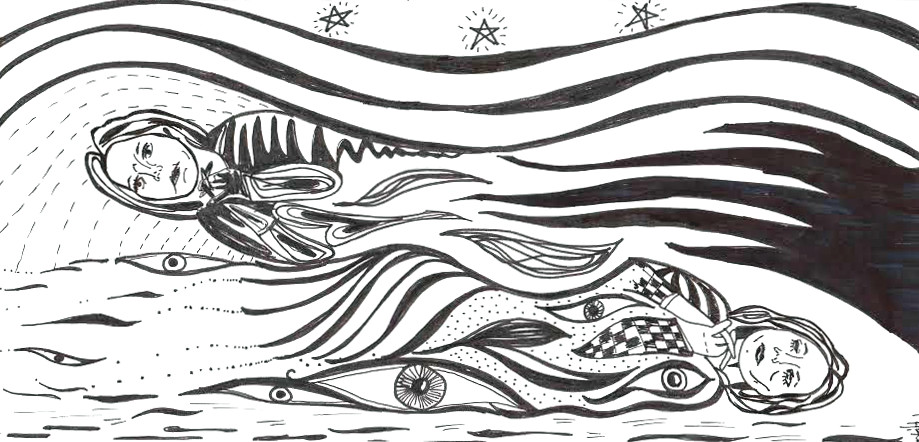

Landscape Illuminated 2 by Philippa Jones

Elizabeth Gilbert, author of Eat, Pray, Love and Big Magic: Creative Living Beyond Fear, notes that our ancestors began painting almost forty thousand years ago but started cultivating crops only ten thousand years ago. This suggests a strong, perhaps hard-wired, urge to create art, an urge even stronger than ensuring a steady food supply.

Curiously, it seems most cave artists—up to three quarters—were women and girls. We don’t know why they did it. We don’t know why we continue to paint, sculpt, choreograph and compose. But we have theories.

To make sense. Tracy Chevalier, author of The Girl with the Pearl Earring, says storytelling puts a frame (real or metaphorical) around everyday incidents. That frame allows us to focus on and make sense of our personal dramas. Research shows that our brains actually crave stories and will construct story-like patterns from almost any event. In a complicated, changing world, we simply think best in stories.

To purge. Aristotle believed theatre, especially tragedy, purged us of negative emotions. We still use his term catharsis to describe cleansing through art. It’s possible our ancestors painted caves as a purgative ritual. Recent evidence suggests writing that vents emotion—mommy blogs, for instance—offers a similar kind of therapy.

To feel better. Storytelling has more specific and measurable health benefits, too. Studies have shown that regular writing and other forms of art can help injuries heal faster, boost immune function, alleviate symptoms of cancer and depression, boost working memory, increase motivation—and even “turn lives around.”

That’s a whole lot of reasons to create stories—and a fair excuse for my stealing away from the lab to craft images of seagulls. So why did I stop? Perhaps because in packing those photos so quickly into boxes and binders I dismissed a further reason, perhaps the reason stories have endured for tens of thousands of years:

To connect. Storytelling, whether through writing, performance or visual art, means forging a relationship between teller and audience. A story is never air-tight and self-contained. Good stories leave blank spots, spaces to be filled through the active process of reading or viewing. It takes both to complete a story. Creating art may empower the artist but filling in those spaces empowers the audience.

In fact, Aristotle’s original notion of catharsis applied to the audience, not the actors and playwrights; he believed theatre purged negative emotions in viewers. Present-day research tends to agree. A study published last year showed that attending live theatre increased “literary knowledge, tolerance and empathy” among students. This one of a growing number studies on the power of stories for the audience. Collectively, they show stories are easier to remember than facts—stories help us learn. More than that, reading, viewing or listening to stories can increase our understanding of others. It can alter deep-seated biases and foster empathy. Look at the phenomenal success of Humans of New York: a twenty-line personal story can stir millions of readers to action.

That’s one gigantic reason to tell stories. But it means actually telling the story. It means embracing the creator-viewer relationship, taking the photos out of the box, the canvas out of the studio, the story off the laptop. It means honing our craft (there’s no way around practice) but, eventually, at some point, sharing our work.

Which is hard.

Most of my photos are still in boxes. I never went back to photography: I graduated, my cameras were stolen, the technology changed. I moved on to writing and again found that thrill of pure creation. And although I’ve posted and published my work many times, that old urge to hoard and safeguard remains. It’s not ready. It’s not original. It will only be rejected.

Putting yourself “out there” is hard, no question. Traditional routes to building an audience—through publishers, agents and galleries—can be particularly tough. Until that fabulous and elusive acceptance letter, it may feel as if no one is listening, that you really aren’t sharing work at all.

But there are other ways to cultivate a vital two-way relationship with viewers.

- Find a writing group or start a new one.

- Take a class, in person or online.

- Open a pop-up store (this works best for visual art, but why not pop-up poetry or performance art?).

- Join an online peer group like SheWrites or Wattpad.

- Write micro-stories on social media.

- Start a blog or post on open sites like Medium or StoryCorp.

You may not want to share everything, and in some cases you shouldn’t. You may still encounter criticism, especially if posting online. But as Brandon Standton of Humans of New York says, telling stories with “a spirit of genuine interest and compassion” tends to bring out the same in viewers. And sharing just some of your work, nurturing even a small audience, may keep you going through moments of doubt.

I said most of my photos would never be seen; most were still in boxes. There are some exceptions. Four are framed and decades after printing still hang on living room walls, two on Canada’s east coast, two on the west. They capture a singular place and time. They’ve been viewed by a few dozen friends and friends of friends. Over the years, they’ve prompted questions, stirred memories, started conversations. Is it enough to build a career? No. Is it enough to keep telling stories? Yes, I think it is.

Many thanks to Scotiabank (Bridgewater, Nova Scotia, branch) for funding this issue of Understorey Magazine.